ecosistemas

ISSN 1697-2473

Open access / CC BY-NC 4.0

© 2025 The authors [ECOSISTEMAS is not responsible for the misuse of copyrighted material] / © 2025 Los autores [ECOSISTEMAS no se hace responsable del uso indebido de material sujeto a derecho de autor]

Ecosistemas 34(3): 3047 [September-December / septiembre-diciembre, 2025]: https://doi.org/10.7818/ECOS.3047

Associate editor / Editora asociada: Raquel Benavides

RESEARCH ARTICLE / ARTÍCULO DE INVESTIGACIÓN

Are tropical forest science and policy disconnected? Assessing the common understanding of the concept of “timber species” among different forest stakeholders in the Amazon

Ximena Herrera-Alvarez1 ![]() ,

Gonzalo Rivas-Torres2

,

Gonzalo Rivas-Torres2 ![]() , Oliver L. Phillips3

, Oliver L. Phillips3 ![]() ,

Vicente Guadalupe4

,

Vicente Guadalupe4 ![]() , Juan A. Blanco1,*

, Juan A. Blanco1,* ![]()

(1) Institute for Multidisciplinary Research in Applied Biology, Dep. Sciences, Public University of Navarre, 31006, Pamplona, Spain.

(2) Estación de Biodiversidad Tiputini, Colegio de Ciencias Biológicas y Ambientales, Universidad San Francisco de Quito, 170901, Quito, Ecuador.

(3) School of Geography, University of Leeds, LS2 9JT Leeds, United Kingdom.

(4) Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organization, Bioamazon Project, Permanent Secretariat, SEPN 510, Bloco A, 3º andar – Asa Norte – Brasília-DF, Brazil.

* Correspondig author / Autor de correspondencia: Juan A. Blanco [juan.blanco@unavarra.es]

|

> Received / Recibido: 10/062024 – Accepted / Aceptado: 06/10/2025 |

How to cite / Cómo citar: Herrera-Alvarez, X., Rivas-Torres, G., Phillips, O.L., Guadalupe, V., Blanco, J.A. 2025. Are tropical forest science and policy disconnected? Assessing the common understanding of the concept of “timber species” among different forest stakeholders in the Amazon. Ecosistemas 34(3): 3047. https://doi.org/10.7818/ECOS.3047

|

Are tropical forest science and policy disconnected? Assessing the common understanding of the concept of “timber species” among different forest stakeholders in the Amazon Abstract: Dialogue among forest actors determines the success of sustainable forest management. However, for such dialogue to be fruitful, common concepts must be shared and agreed among different parties. Hence, we aimed to understand how the concept of “tropical timber species” is created and shared among forest actors, using the Amazon region as a study case. A systematic review in Web of Science and Scopus (1980-2023) was carried out to identify different definitions of tropical timber species. In addition, a survey was conducted among forest administrations to elucidate how the concept of timber species is used by each national authority. Results were categorized and compared with definitions of timber species by international forest organizations such as FAO and ITTO (International Tropical Timber Organization). The systematic review detected a surprisingly low number of scientific papers (31) mentioning a definition of timber species. Four main thematic categories associated with the timber species concept were identified: economical, ecological, aesthetic and wood properties. Meanwhile, all forest administrations mentioned the lack of official concept or definition on timber species. However, both forest scientists and policymakers associated similar thematic categories to the concept of timber species. In addition, responses from national departments did not align with timber species definitions by international organizations. In all, while common ground was identified among different forest actors, such understanding is not included in official documentations, and the lack of consistent definitions is likely to be a factor inhibiting the effective application of science-based sustainable forest management in the Amazon. Keywords: Amazon region; harmonization; policy makers; timber species; systematic review; tropical forest ¿Están las ciencias y las políticas forestales desconectadas? Evaluando la comprensión común del concepto de “especie maderable” entre los diferentes actores forestales en la Amazonía Resumen: El diálogo entre los actores forestales determina el éxito de la gestión forestal sostenible. Sin embargo, para que ese diálogo sea fructífero, las diferentes partes deben compartir y acordar conceptos comunes. Por lo tanto, nuestro objetivo en este trabajo ha sido comprender cómo se crea y comparte el concepto de “especies maderables tropicales” entre los actores forestales, utilizando la región amazónica como caso de estudio. Para ello se realizó una revisión sistemática en Web of Science y Scopus (1980-2023) para identificar diferentes definiciones de especies maderables tropicales. Además, se llevó a cabo una encuesta entre las administraciones forestales para dilucidar cómo utiliza cada autoridad nacional el concepto de especie maderable. Los resultados se categorizaron y compararon con las definiciones de especies maderables de organizaciones forestales internacionales como la FAO y la OIMT (Organización Internacional de las Maderas Tropicales). La revisión sistemática detectó un número sorprendentemente bajo de artículos científicos (31) que mencionasen una definición de especie maderable. Entre dichos artículos, se identificaron cuatro categorías temáticas principales asociadas con el concepto de especie maderable: propiedades económicas, ecológicas, estéticas y de la madera. Mientras tanto, todas las administraciones forestales amazónicas mencionaron la falta de un concepto o definición oficial sobre especies maderables. Sin embargo, tanto los científicos forestales como los responsables de la formulación de políticas asociaron categorías temáticas similares al concepto de especies maderables. Además, detectamos que las respuestas de los departamentos nacionales no se alineaban con las definiciones de especies maderables de las organizaciones internacionales. En total, si bien se identificaron puntos en común entre los diferentes actores forestales, ese entendimiento no está incluido en la documentación oficial, y la falta de definiciones consistentes probablemente sea un factor que inhiba la aplicación efectiva del manejo forestal sostenible con base científica en la Amazonía. Palabras clave: región amazónica; armonización; formuladores de políticas; especies maderables; revisión sistemática; bosque tropical |

Introduction

Tropical forests are one of the largest biomes in the world, covering 1949 MHa of the Earth's land surface (Pan et al. 2011). These forests are among the most diverse and productive ecosystems on the planet but face multiple challenges to maintain their ecosystem services, including climate change (Pan et al. 2013), the expansion of commercial agriculture (Dinerstein et al. 2015), and illegal timber logging (Ferrer Velasco et al. 2020). Even though forests are mostly considered as “common goods” and they benefit to all members of society (Esperon–Rodriguez 2024), governments are responsible for developing legal frameworks exercising national sovereignty and stewardship of the forest resource within their jurisdictional borders (Hardle-Wolfson and Quinteiro 2022). However, for such frameworks to be effective in implementing sustainable forest management, a functional articulation of diverse tropical forest actors is needed to allow effective information flows (FAO 2002). The use of common concepts to bridge communication barriers between different actors is thus of paramount importance (Ducamre et al. 2021). This is especially so in and among tropical countries where the communication of scientific information for evidence-based policymaking is poorly institutionalized (Jones et al. 2008). In fact, examples of poor implementation of forest conservation laws due to lack of adequate definitions have been already reported for the Brazilian Amazon (Guimarães Vieria et al. 2014). Similarly, confusion surrounding the “forest degradation” concept is preventing administrative actions in Ecuador (OTCA 2019), even if such definition already exists at international level (FAO 2018). Such facts call for harmonizing indicators and definitions in scientific and administrative literature (Failing and Gregory 2003; Zalles et al. 2024). Indeed, important definitions affecting forest management such as “forests”, “forest degradation”, or “plantation” have received extensive attention both academically (i.e. Helms 2002; Lund 2002; Chazdon et al. 2016), and institutionally (i.e. FAO 2018), resulting in specific and even quantitatively limited definitions that have allowed a quasi-standardization of such terms in many forest and environmental laws around the world. However, even for these well-developed concepts, calls for harmonizing definitions also exist (Zalles et al. 2024). Therefore, in the case of other concepts that are less studied and that lack such conceptual development and standardization, such as “timber tree species”, it is even more urgent to reach such a common understanding among forest actors. “Tropical timber tree species” is a key concept in sustainable forest management, as it connects scientific information linked to “species” (i.e. taxonomy, ecological requirements, genetics) with operational concepts linked to “timber” (i.e. harvesting, selective logging), and also market and trade regulations and conservation efforts (i.e. lists of endangered species). Therefore, due to the little work done so far to harmonize this concept (Herrera-Alvarez 2024), our work focuses on how forest actors understand such concept.

Previous work suggests that an important motivation of forest owners to work with other actors is to obtain and learn new information (Ruseva et al. 2014). Indeed, an inability to successfully transfer such information is often a limiting factor inhibiting the transition towards sustainable forest management (Zafra-Calvo et al. 2018). In addition, those actors with more relationships and success in interchanging knowledge have more power to trigger significant changes (Borgatti and Cross 2003). In all, as reliable information and its exchange are the basis of science-based forest management (Racelis and Barsimantov 2013), it is critically important to understand how forest scientists, national forest departments and international forest organizations interpret the concept of “tropical timber species”.

Examples of the problems caused by the lack of a common formal definition of timber species can be found in literature. For example, although in Peru a legal system for traceability and wood origin is already in place (MINAGRI 2015; SERFOR 2024), the absence of a timber definition at species level has facilitated illegal logging, by labeling products as non-timber or by mislabeling the region of origin. In fact, journalist investigations revealed that timber shipments, including species like mahogany and cedar, were exported without proper documentation, often from areas not inspected by authorities (Conniff 2017). In Ecuador, the lack of a clear definition for timber species has led to challenges in forest management and conservation, with approximately 26 % of analyzed forest species in the region lacking an IUCN assessment, complicating conservation and management efforts (López-Tovar et al. 2024). In Brazil, low-density species such as Manilkara huberi are heavily exploited. Current legislation mandates that at least three individuals of each species be left per 100 hectares during logging (MMA 2006). For species with such low densities, this requirement renders legal logging unfeasible, pushing loggers toward illegal activities or the exploitation of less-desirable species, thereby compromising forest sustainability (Lima et al. 2024). In several countries, the national legislation classifies and tracks timber products or wood origins (Table 1), but this is less effective than classifying timber species, as products could be classified as non-timber, or their origin can be more easily manipulated than the taxonomic nature of timber, which can always be tested by different botanical, dendrological or genetic tests.

Hence, a question emerges: is there in fact a common understanding among relevant forest actors of what a tropical timber species actually is? In other words, how differently do different stakeholders define timber species; and are there any common points among such definitions? To solve these questions, we have focused our work on understanding how three main forest actors understand the concept of “tropical timber species”. These are: 1) forest scientists, as they generate new information, 2) forest policymakers (i.e. national forest administrations) being the ones that monitor and implement regulations at national level, and 3) international organizations, as they coordinate supranational efforts on regulating trade, conservation, management and knowledge, and have the capacity to translate scientific knowledge into effective supra-national policies and criteria for management.

Given the complexity of dealing with multiple forest administrative organizations in tropical countries, we used as a study case the Amazonian region as it stands out as the largest continuous tropical forest in the planet (Pitman et al. 2001) and thus deserves particular attention. In addition, despite the Amazon region having at least 4000 tree species with potential timber value, only 1112 are listed as timber species by national authorities (Herrera-Alvarez et al. 2024), from which less than 300 species are actually utilized (Samanez-Mercado 1990). National markets exist for only about 50 species, and only a fraction are traded internationally. Therefore, the lack of a standardized definition for timber species contributes to this underutilization, limiting economic opportunities and sustainable forest management. In addition, the ongoing commercial timber demand from this biome is important at world level (ITTO 2021) and substantial illegal logging is widely reported in Amazonian countries, affecting forest conservation (OTCA 2019).

We initially hypothesized that there would be a lack of agreement concerning the tropical timber species concept among forest actors. To assess this hypothesis, we carried out a systematic review of scientific literature combined with a survey of all Amazonian national forest administrations to identify the definitions used by scientists and policy makers. In addition, we reviewed the definitions used by relevant international organizations, institutions and secretariats which belong to the Collaborative Partnership on Forests (CPF 2025). We then compared the common and different points among all these actors.

Table 1. Relevant legal frameworks applicable to Amazonian timber species.

Tabla 1. Cuerpos legislativos relevantes aplicables a las especies maderables amazónicas.

|

Country |

Legal framework |

References |

|

Bolivia |

A digital certificate of forest origin supports transport, storage and commercialization. |

|

|

Brazil |

Operational limitations set a minimum retention of 10 % of eligible trees and at least three trees per species per 100 ha. Harvest licensing requires species-level data for transport and storage. Management plans require minimum cutting diameters. |

|

|

Colombia |

Inventories and management plans require species-level parameters, but “timber” is not included as a species trait. |

|

|

Ecuador |

A legal provenance certificate aims to track harvested wood. |

|

|

European Union |

Nomenclature required (scientific and common) for all timber products. |

|

|

French Guyana |

Minimum cutting diameters required at species level. Low-impact logging prescriptions required for management plans. |

|

|

Guyana |

Code of Practice for Forest Operations regulates planning and verification by species. The Removal Permit allows a log-tracking system. |

|

|

Peru |

Forest Management Regulation governs harvesting and mobilization. Forest Transport Guidelines in place regulating timber movement. Official Species list includes standardization of nomenclature, but not definition of timber species. |

|

|

Suriname |

The Forest Management Act and the Code of Practice require species-level minimum cutting diameters and harmonized scientific names. A log-tracking system is in place (LogPro) |

|

|

Venezuela |

Circulation permits are required for all forest products. An electronic guide system in place to document transport. |

Materials and Methods

The concept of timber species by scientists

A systematic review using the PRISMA guidelines (Page et al. 2021) was carried out following the four steps described below.

Step 1. Identification

Queries in the Web of Science (https://www.webofscience.com/wos) (including the Core Collection, the Book Citation Index, MEDLINE, CAB abstracts, ScIELO Citation Index and Korean Citation Index), and the Scopus databases (https://www.scopus.com) were carried out. Access to both databases was carried out through the national license for Spanish institutions (FECYT: https://www.recursoscientificos.fecyt.es/). In order to have a broad perspective of timber species definition, the Boolean operator “timber species definition” OR “timber species concept” was used in both academic databases in the fields "title”, “keywords” and “abstract” during the period of 1980–2023. This period was selected because in 1980 the tropical forestry world began to get organized institutionally with the creation of the first International Tropical Timber Agreement (ITTO 2009), and 2023 was the last year of fully corrected and updated records available at the time of carrying out the search (November 2024).

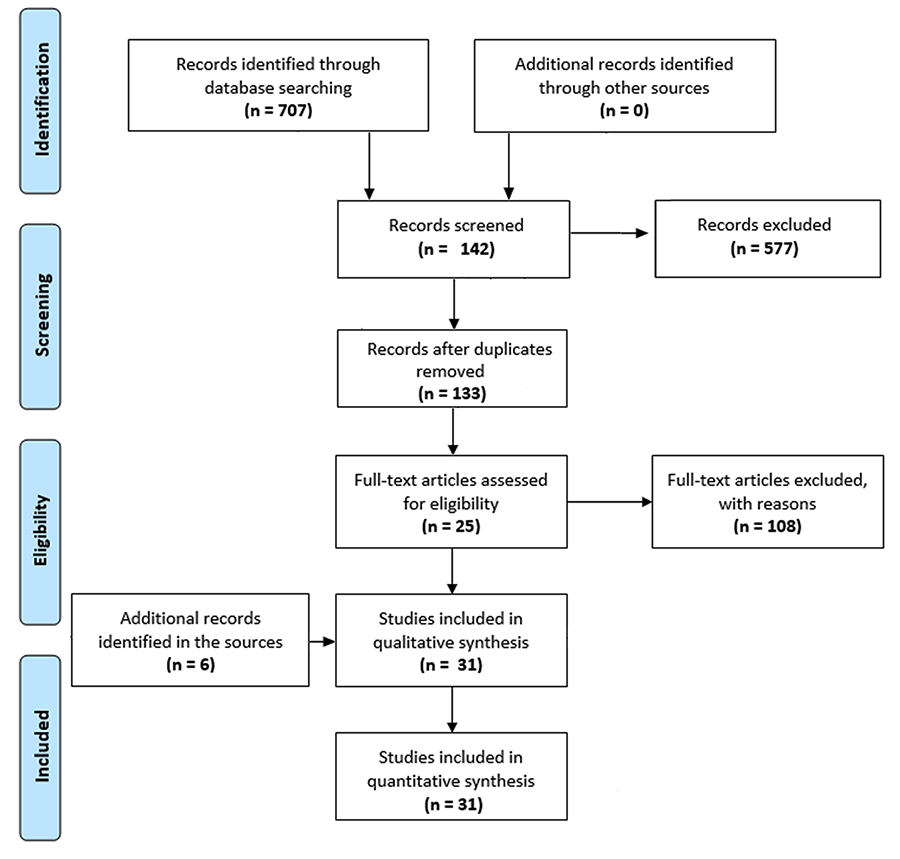

For the Web of Science, documents included in the search were articles, books, and reviews published in English and included in the following categories: Forestry, Biodiversity Conservation, Materials Science, Environmental Sciences, Ecology, Plant Sciences and Agriculture (Table A1 in the Appendix). In Scopus, documents included in the search were articles, reviews, book chapters and books published in English at their final publication stage (i.e. no preprints). In addition, documents were further selected by their main topics, being the ones selected Agricultural and Biological Sciences, Earth and Planetary Sciences, Environmental Science, Materials Science, Multidisciplinary and Social Sciences (Table A2 in the Appendix). Because of both queries, 707 different records from both databases combined were identified (Fig. 1).

Step 2. Screening and exclusion

Once 707 potential documents were identified, the search was refined using several exclusion criteria (see sections 1 & 2 of the Appendix). In total, 577 references were excluded. In addition, nine duplicated references were identified. Finally, four references were not available because of lack of accessibility to the full text source. Consequently, at the end of the screening process, 133 documents were identified and retained for their use in the next step (Fig. 1).

Step 3. Eligibility

The 133 identified references went through a manual eligibility check in which definitions or comments on “timber species” or “tropical timber” were identified as requirement. As a result, we excluded 108 documents that did not mention “timber species” in their full text, resulting in 25 documents that fulfilled this criterion being retained. In addition, when manually reviewing the full text of these references, citations to six more relevant documents that were not initially identified in the queries were identified and included. Therefore, for the final analysis 31 different documents were used (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram indicating the steps followed to create a database on the definition or explanation of the concept of timber species (identified records from combined Web of Science and Scopus searches).

Figura 1. Diagrama de flujo según PRISMA indicando los pasos seguidos para crear una base de datos con la definición o explicación del concepto de “especie maderable” (los registros identificados combinan las búsquedas en Web of Science y Scopus).

From the 31 published documents analyzed, we extracted information related to the use of the “timber species” concept. Relevant comments were grouped in four thematic categories according to the following criteria: Ecological (i.e. species ecophysiological traits, attributes or similar); Economical (i.e. information related to market, profitability, economic value or similar attributes); Aesthetic (i.e. color, texture, smell, or similar attributes); Wood properties (i.e. physical, mechanical or similar attributes); and Others (attributes not fitting in the previous categories). Although such categories may be interdependent (i.e. economic value is linked to wood properties) we decided to use such categories as they provide direct insights on the main criteria as understood by the original documents authors and also allowed the comparison with results from surveying national forest authorities (see below).

To code the content of each document, we marked with “1” the presence of information in the document related to such criterion in relationship with the concept of “timber species”, and with “0” the absence. Categories were not exclusive, and hence information from a single document could be then coded into several categories. Then, we calculated the total score for each criterion by adding all the presences, as well as estimating for each category the percentage of the total number of presences. Finally, the text containing the main information related to timber species was also identified, extracted, and grouped into thematic categories.

The concept of timber species by forest administrations

To assess how the concept of timber species was used by forest administrations in the Amazonian countries, during the months of April 2020 and June 2021, we requested by email to each Forest Department from all nine Amazon countries and territories (Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela, Guyana, Brazil, Suriname, and French Guiana) the timber species definition, concept, or criteria they used (see section 3 of the Appendix). Replies were obtained from all Amazon countries except French Guiana and Guyana.

Responses were classified according to the same thematic categories found after the systematic review of scientific literature (Ecological, Economical, Aesthetic, Wood properties, and Others). Administrative replies were coded for presence or absence of each thematic category. Then, the total number of responses for each thematic category was recorded. In addition, the percentage of the total number for each category was estimated (Table A4 in the Appendix).

The concept of timber species by international institutions

A search of the terms “timber species definition/concept” or “tropical timber definition/concept” was also carried out in the glossaries of the 16 international organizations, institutions and secretariats belonging to the Collaborative Partnership on Forests (CPF). In this context, it was identified whether the international organization has a glossary or similar, and if so, whether their glossaries contained a concept or definition on the subject (Table 2).

Results

The view from scientists

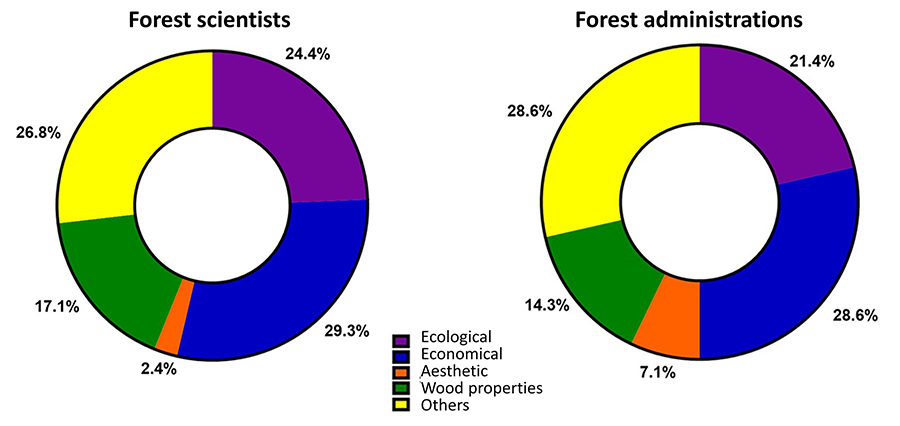

Information used in association with the concept of timber species were mainly distributed in four thematic categories, with any additional information outside these categories coded as “Others”. Ten documents were related to Ecological information (24.4 %), 12 documents related to Economic topics (29.3 %), one document related to Aesthetic information (2.4%), seven documents related to Wood properties (17.1 %) and 11 documents did not provide specific information (Others: 26.8 %), even if they met all the inclusion criteria (Fig. 2).

As part of the Ecological thematic area, information related mainly to terms such as ecological traits, population variables, timber units and ecological requirements for timber species was identified. Regarding the Economical thematic area, the main topics were wood prices, timber markets, productivity, commerce, high-value, export value, marketable sizes, local value and valuable timber. Considering Aesthetic topics, information related to beauty of the tree and aesthetics of their timber was the dominant. In the context of Wood properties, most of the information related was about physical and mechanical characteristics such as density, strength, shrinkage, durability and high-quality timber (Table 2).

The view from the Amazonian forest administrations

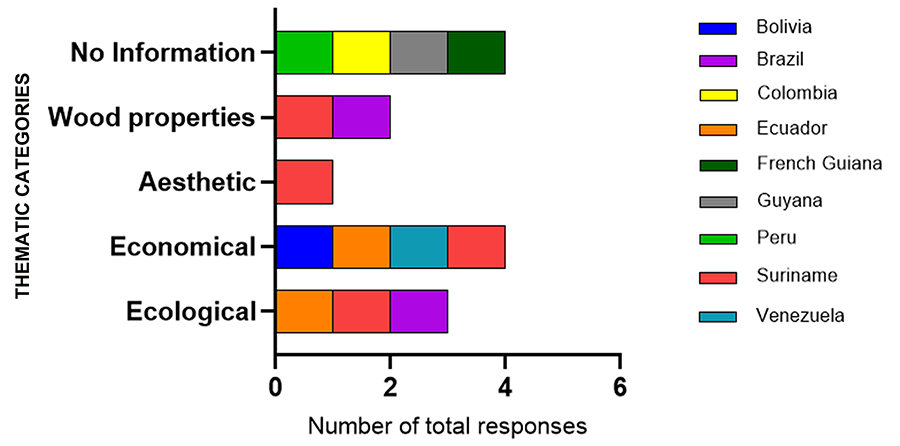

We identified five countries (Bolivia, Brazil, Ecuador, Suriname, and Venezuela) that had an unofficial and internal definition or concept for timber species but lacked official or institutionalized concepts or definitions. In addition, Colombia and Peru mentioned that they do not have a specific concept or definition of timber species being used even unofficially at institutional level. Finally, it was not possible to obtain a response from Guyana and French Guiana. In general, most of the responses were related to Economical information (28.6 %), Ecological information (21.4 %), Wood properties (14.3 %), and Aesthetic information (7.1 %), and 28.6 % of responses related to other topics (Fig. 2).

In addition, four of the five countries using an unofficial definition of timber species (Bolivia, Ecuador, Suriname and Venezuela) reported that timber species concept is mainly related to Economical information. Only three (Brazil, Ecuador and Suriname) reported in their responses that Ecological information related to timber species definition, two (Suriname and Brazil) invoked Wood properties whilst only Suriname mentioned Aesthetic information in their response (Fig. 3).

Figure 2. Main topics used in the conceptualization of timber species by scientists (left panel) and by forest administrations (right panel). Ecological: species ecophysiological traits, attributes or similar attributes; Economical: information related to market, profitability, economic value or similar attributes; Aesthetic: color, texture, smell, or similar attributes; Wood properties: physical, mechanical or similar attributes. Others: topics not included in the previous categories.

Figura 2. Principales temas utilizados en la conceptualización de especies maderables por científicos (panel izquierdo) y por administraciones forestales (panel derecho). Ecológico: rasgos, atributos o atributos similares ecofisiológicos de la especie; Económico: información relacionada con el mercado, rentabilidad, valor económico o atributos similares; Estético: color, textura, olor o atributos similares; Propiedades de la madera: atributos físicos, mecánicos o similares. Otros: temas no incluidos en las categorías anteriores.

Table 2. Categorization of the information on timber species conceptualization extracted from the systematic review of scientific literature.

Tabla 2. Categorización de la información sobre conceptualización de especies maderables extraída de la revisión sistemática de la literatura científica.

|

Categories |

Information related to timber species |

References |

|

Ecological |

High root-taking capacity, fast growth, special site requirements, commonness, rareness, shade-tolerance, seral species, relative densities, site quality, |

Steele et al. (1983); Kennard and Putz (2005); Schulze et al. (2008); Hein (2009); Spiecker et al. (2010); D’Oliveira and Ribas (2011); Gunatilleke (2015); Ptichnikov and Martynyuk (2020); Vaca et al. (2022) |

|

Economical |

High good prices, timber market characteristics, productive, commercial, high-value, export value, marketable sizes, local value, valuable, wood volume |

Keating (1980); Steele et al. (1983); Teel and Lassoie (1991); Condit et al. (1995); Karsenty and Gourlet-Fleury (2006); Schöngart (2008); Schulze et al. (2008); Hein (2009); Geldenhuys (2010); Richards and Schmidt (2010); Agyeman et al. (2016); Vaca et al. (2022) |

|

Aesthetic |

Beauty of the tree, aesthetics of their timber |

|

|

Wood properties |

Density, strength, shrinkage, durability, high - quality timber for mechanic or industrial uses |

Keating (1980); Condit et al. (1995); Schöngart (2008); Arriaga et al. (2012); Schulze et al. (2008); Rohana et al. (2010); Oum Lissouck et al. (2016) |

Figure 3. Number of responses by forest departments from the Amazonian countries associated with timber species conceptualization grouped according to thematic categories obtained after the systematic review.

Figura 3. Número de respuestas de los departamentos forestales de los países amazónicos asociadas a la conceptualización de especies maderables agrupadas según categorías temáticas obtenidas después de la revisión sistemática.

The view from international organizations

Fourteen of the international organizations belonging to the Collaborative Partnership on Forests (CPF) have a glossary in their web pages, the exceptions being the Green Climate Fund and the UN´s Department of Economic and Social Affairs. However, we found that only two organizations (FAO and ITTO) mention information related to a concept or definition of timber species or tropical timber (Table 3). FAO defines “timber producing species” or “timber tree” as “any species that is valued as a source of timber” (FAO 2013). In addition, ITTO describes two similar concepts: tropical timber and timber tree. Considering “tropical timber”, it is defined as “those used for industrial purposes, which grow or are produced in the countries situated between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn. The term cover logs, sawn wood, veneer sheets and plywood” (ITTO 2013), while a “timber tree” is considered as being “one felled for its wood for use in construction or production of wooden items such as flooring, furniture, musical instruments and carvings. Felled trees may be traded in the form of primary wood products such as roundwood or smaller, cut logs (sawnwood), or in the form of finished products such as veneer, boards, plywood or wooden objects” (ITTO 2012).

Table 3. Tropical timber definition (including alternative spellings) in each partner of the Collaborative Partnership on Forests (if any available).

Tabla 3. Definición de madera tropical (incluidas ortografías alternativas) en cada socio de la Asociación de Colaboración sobre Bosques (si hay alguna disponible).

|

Institution |

Glossary or similar |

Timber/wood species concept or definition |

Reference |

|

Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) |

Yes |

No |

|

|

Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) |

Yes |

No |

|

|

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) |

Yes |

No |

|

|

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) |

Yes |

Yes (see main text) |

|

|

Green Climate Fund (GCF) |

No |

No |

|

|

Global Environment Facility (GEF) |

Yes |

No |

|

|

International Timber Trade Organization (ITTO) |

Yes |

Yes (see main text) |

|

|

International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) |

Yes |

No |

|

|

International Union of Forest Research Organizations (IUFRO) |

Yes |

No |

|

|

United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification |

Yes |

No |

|

|

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) |

Yes |

No |

|

|

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) |

Yes |

No |

|

|

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs |

No |

No |

|

|

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change |

Yes |

No |

|

|

World Agroforestry |

Yes |

No |

|

|

The World Bank |

Yes |

No |

Discussion

On the lack of a harmonized definition of tropical timber species

Our initial hypothesis on the lack of harmonization related to the use of the “tropical timber species” concept by relevant forest actors can be partially accepted, as a clear and precise definition of timber species was neither found nor shared by two or more forest actors. However, there were similarities in the main topics related to such concept in the three types of actors analyzed. It is somehow surprising that such an important topic as “timber species” lacks an adequate theoretical support or a clear and well-recognized formal written definition. This is particularly important, as it is clearly an interdisciplinary concept, as shown by the lack of clear dominance of the main topics related (i.e. Ecological, Economic and Wood properties). In fact, such inherent interdisciplinarity may be the origin of the lack of a specific definition, due to the difficulty to accommodate visions from all relevant fields (MacLeod 2016). In this regard, Venezuelan forest authorities reported the issue of working with confusing definitions even for seemingly common terms such as “forests”. The use of different terms for “timber species” has already been mentioned as an impediment to systematize forest information in the Amazon basin (OTCA 2019).

The importance of having a standardized concept of “tropical timber species” is highlighted when considering its links to other relevant management concepts. First, it is directly linked to the concept of “forest”, since “timber species” specifies which tree taxa within tropical ecosystems are formally recognized as subject to harvest and management (Herrera-Alvarez et al. 2024), thereby shaping how forests are inventoried, regulated, and conserved. Second, it is closely tied to the concept of “forest degradation”, as selective logging (Asner et al. 2005) is assessed precisely in relation to the extraction intensity of timber species in several Amazonian national legislations (see new Table 1). Hence, without a shared definition, it becomes difficult to distinguish sustainable use from degradation caused by overharvesting of high-value taxa (Chazdon et al. 2016; Zalles et al. 2024). Third, the timber species notion underpins sustainability indicators such as minimum cutting diameters, species-specific retention thresholds, and regeneration monitoring, all of which require clarity on what qualifies as a timber species and hence which species are object of the current legislations (Table 1). In this way, the concept of tropical timber species should not be considered as an isolated definition but rather an operational category that directly supports the measurement, regulation, and long-term sustainability of tropical forests, being more specific that other related concepts such as “tropical wood” or “tropical timber products”, which are not taxonomically defined.

Nonetheless, missing a clearly published definition (either scientifically or institutionally) is not unique to timber species, as a similar situation has been identified for concepts such as biodiversity (Andrés et al. 2022). This supports the need for assessing the common ground in topics of interest among scientists and policy makers, as a lack of mutual communication among different and well-separated categories of actors has been identified in participatory process in forestry (Blanc et al. 2018).

Similarly, a “timber species” concept or definition was not institutionally recognized or stated in any of the official documents consulted and provided by the national forest administrations. In fact, most (if not all) were unofficial operational concepts or definitions being assumed by the respondents at the personal level but not specifically stated or based on clear tree biophysical features. Nevertheless, it is important to point out that Amazonian policy makers share with forest scientists a quite similar basic understanding of the thematic categories related to the concept of timber species, fulfilling an important first step to design more science-based and society-relevant sustainable forest management (Leach and Fairhead 2025).

It is relevant to highlight that Suriname was the only country that included most of the thematic categories identified in scientific literature. Then, Brazil included in its response information related to Ecological information and Wood properties. In addition, most of the countries (Bolivia, Ecuador, Suriname and Venezuela) agreed that the development of the concept of timber species was related to the availability of Economical information, combined with information on Ecological aspects in the cases of Brazil, Ecuador and Suriname. Unfortunately, we were not able to include information from Peru, Colombia, Guyana and French Guiana due their lack of response to this specific question. Our results therefore highlight the lack of common understanding, as different administrators in different countries have different concepts.

The importance of establishing a clear definition of tropical timber species becomes evident when considering its direct implications for forest governance and trade. In Amazonian countries, regulations apply species-specific parameters such as minimum cutting diameters, retention thresholds, and requirements for transport and commercialization permits (Table 1). Without a harmonized definition of what species can be considered as timber species, these rules are implemented inconsistently, generating loopholes that weaken legality verification and sustainable management. At the international level, the EU Deforestation Regulation now requires operators to report both the scientific and common names of all timber species in their supply chains (European Union 2023). This means that if timber trade from the Amazonian regions (or other) are not properly classified as timber species, it becomes difficult to comply with EU´s market regulations. The importance of using a clear definition of “timber species” is based on the knowledge linked to tropical species, which encompasses taxonomic, ecological, genetic and other knowledge. By clearly classifying tree species in timber and non-timber, forest management, inventory and conservation, as well as timber trade and transport, can be much clearer and more specific than when such activities are based on definitions of products or regional origins, which are subject to personal interpretations or manipulations.

The lack of specific definitions of timber species at administrative levels could have one, few, or multiple explanations. Some of these may include: 1) Science not being routinely used by public institutions or policy makers (Sienkiewicz and Mair 2020); 2) Knowledge transfer from scientists to policymakers and international organizations not being carried out efficiently (Pulido-Salgado and Castaneda Mena 2021; Jones and Walsh 2008; McNeal et al. 2020); 3) A lack of financial and human resources, gaps in data, and difficulty to access to scientific information for policymakers (Theokritoff 2018); 4) Scarcity of opportunities where scientists, policymakers and international organizations can meet and exchange information and ideas (Washbourne et al. 2024); 5) Language barriers, as English documents can be an obstacle for their use if policymakers work in other official languages (Daramola et al. 2024; Hwang 2013; Suaa et al. 2024); 6) A lack of incentives (mainly funding) to support joint work of scientists and policy maker, at least in the Amazonian countries (Choi et al. 2005); 7) Different perspectives and interests by scientists, policy makers and other stakeholders (Ramirez and Belcher 2019; Ozga 2024); and 8) Low readiness on the part of policy-makers to solicit and embrace expert advice when formulating policies (Murphy et al. 2022).

At the supranational level, it is important to mention that even if most organizations belonging to the CPF have their own glossaries, only FAO and ITTO have a brief definition for timber species, albeit quite broad. In addition, none of the Amazonian countries reported in their responses the official definition of timber species, neither their own national definitions nor adhering to the ones by international institutions. This indicates that effective communication between international organizations and national forest departments is likely not effective enough. In this sense, the Leticia Pact, signed in 2019, was an effort in which all member countries of the Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organization (ACTO) except Venezuela and French Guiana reaffirmed their commitment to reinforce initiatives that promote solutions to challenges such as deforestation and forest degradation. For this purpose, coordinated actions against deforestation supported by legal frameworks and national policies (Gobierno de Colombia 2020) are required, as well as by updated scientific knowledge. In fact, a regional agreement to prevent illegal logging for the Amazonian countries was signed in 2023 by the Andean Parliament, composed by Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru (Andean Parliament 2023). Therefore, there is an evident need for capacity building among stakeholders. In addition, there is a need to train and support “knowledge brokers”, able to transfer knowledge from academicians to policy makers and forest managers, and that can have an impact on the inclusion of science-based knowledge into regional initiatives and legal frameworks (Theokritoff 2018).

Improving information flows among tropical forest actors: a framework

Although efforts have been carried out in the tropics at different levels to fill the communication gap among stakeholders, effective governance is required with multi-sectoral and multi-actor planning, and representation of sectors involved in forest management and conservation (Muthoni 2002). Recent developments are moving towards such goal, as for example the Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organization (ACTO), the Inter-American Development Bank´s Amazonia Forever initiative, the World Bank´s Amazon Sustainable Landscape program, or the World Resources Institute & World Conservation Society´s Amazon Restoration.

We have shown that an initial common understanding of the criteria related to timber species definition is already in place, but a specific, univocal and clear verbalization of such criteria and the related definition of timber species is still needed. Such definitions, based on theoretical justifications and empirical data, are the foundations of science and the generation of science-based forest management (Dobšinská et al. 2025), and can be used for legal documents, which are in turn the main policy-making instruments. In this context, the establishment of The Science Panel for the Amazon (2021) to guide decision-making with research, technology, and knowledge management, or the establishment of the Science Panel for the Congo Basin (2023), responding a call by central African environment ministers in 2021 (SDSN 2023), are encouraging steps towards improving the science-policy interface in tropical countries. In fact, a commonly recognized definition adopted by the Science Panel for the Amazon could be an important first step to harmonize information among all Amazonian countries, such as the example of National Forest Inventories previously discussed by FAO (2020).

Although the creation of such high-level consulting bodies highlights the need to widen and reinforce the weak common ground among forest actors, we have found through that public administrations are aware of this issue and not that far from scientists’ views. The recent creation of scientific panels is likely a reflection of this fact. Scientific panels and research-based organizations such as CIFOR-ICRAF or IUFRO, are creating venues where scientists can inform policymakers and international organizations, and where policymakers or international organizations communicate their practical needs to researchers (UN 2007). Nevertheless, while the rationale behind evidence-based policy suggests that researchers should provide guidance to policymakers on specific issues based on available evidence, it is imperative that researchers also get involved in the assessment of the policies or regulations carried out by the policymakers, at least in the initial or implementations phases (Ozga 2004).

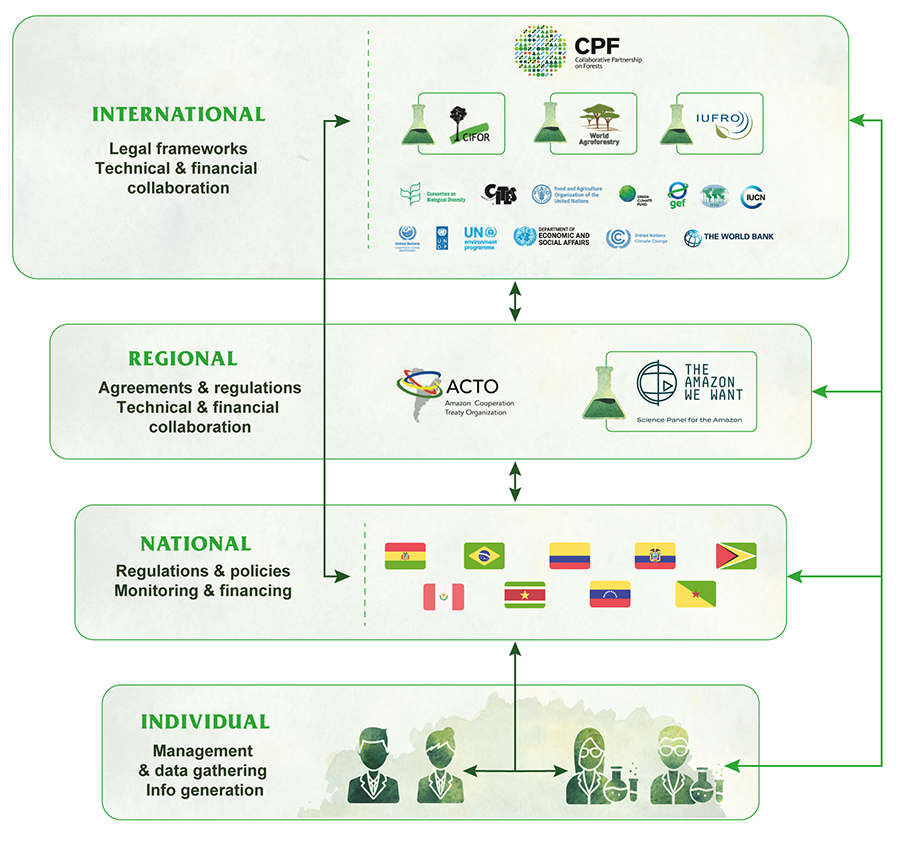

Our research indicates that interconnected approaches are also needed, such as ecological, economical, but also social involving all actors (Hariram et al. 2023). A suggested information flowchart among forest actors in the Amazon is presented (Fig. 4). Such framework could develop and agree on an official, harmonized definition of tropical timber species and later promote its use. We propose as initial definition to be discussed and refined in this framework the following:

Tropical Amazonian timber tree species are those tree species found inside the Amazonian basin at elevations lower than 1000 m.a.s.l., in forest formations, belonging to a variety of plant families, mainly abundant and frequent at local level. These species are located in all forest types but mainly “in terra firme” and swamp forests. In addition, these species usually have many uses beyond timber, and therefore can have a wide range of wood density” (based on work by Herrera-Álvarez 2024).

Such concept could become a keystone to build constructive dialogue on sustainable approaches to improve Amazonian forest management, including the prevention of deforestation and forest degradation (Gandour 2001; Carvalho et al. 2019).

Figure 4. Suggested flowchart of information (black arrows: legal frameworks and policies; red arrows: scientific information) among forest actors (individual scientists and administrators, national authorities, regional forums, and international institutions, including those research-based, marked with flasks) for the Amazonian countries (own elaboration).

Figura 4. Diagrama de flujo de información sugerido (flechas negras: marcos legales y políticas; flechas rojas: información científica) entre los actores forestales (científicos y administradores individuales, autoridades nacionales, foros regionales e instituciones internacionales, incluidas aquellas basadas en la investigación, marcadas con matraces) para los países amazónicos (elaboración propia).

Conclusions

A clear definition of the “tropical timber species” concept was not found in academic sources. Similarly, almost all Amazonian forest authorities reported using unofficial definitions of tropical timber species, or vague definitions provided by international organizations. However, the three main groups of actors (forest scientists, policy makers, and international institutions) linked the use of the “tropical timber species” concept to similar themes, mostly Economic and Ecological information, and, to a less extent, Wood properties. Overall, the results presented here suggest that even though there is a lack of a harmonized and precise formal definition of tropical timber, there is clear common ground for developing such concept, which could support successful dialogue among forest actors in the Amazonian basin. Developing such dialogue is imperative to support sustainable forest management practices to face forest current forest degradation in the region.

Authors' Contribution

Ximena Herrera-Álvarez: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – Original draft, Funding acquisition. Gonzalo Rivas-Torres: Conceptualization, Writing – Review and editing, Supervision. Oliver L. Phillips: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – Review and editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Vicente Guadalupe: Conceptualization, Writing – Review and editing. Juan A. Blanco: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing – Review and editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data that supports the findings of this study will be made accessible on request to the contact author.

Financing, required permits, potential conflicts of interest and acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Public University of Navarre, through a graduate student grant, the Government of Navarre through a travel grant and the University of Leeds through a hosting grant, all awarded to X.H.A.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

ABT (Autoridad de Bosques y Tierra) 2019. Certificado Forestal de Origen Digital para exportación de productos forestales (CFO-D). La Paz, Bolivia.

ABT (Autoridad de Bosques y Tierra) 2025. Resolución Administrativa N° 061/2025. Requisitos actualizados para transporte forestal. La Paz, Bolivia. https://abt.gob.bo/images/stories/formulariosyreglamentos/2025/RA-ABT-061-2025.pdf

Agyeman, V.K., Addo-Danso, S.D., Kyereh, B., Abebrese, I.K. 2016. Vegetation assessment of native tree species in Broussonetia papyrifera-dominated degraded forest landscape in southern Ghana. Applied Vegetation Science 19(3), 498–507. https://doi.org/10.1111/avsc.12241

Andean Parliament 2023. Recomendación No. 511. Marco Normativo para la lucha contra la tala ilegal y comercio asociado en los bosques Amazónicos de la región Andina. Gaceta Oficial del Parlamento Andino. Bogotá, Colombia.

Andres S.E., Standish R.J., Lieurance P.E., Mills C.H., Harper R.J., Butler D.W., et al. 2023. Defining biodiverse reforestation: Why it matters for climate change mitigation and biodiversity. Plants People Planet 5(1), 27–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppp3.10329

Arriaga, F., Íñiguez-González G., Esteban M., Divos F. 2012. Vibration method for grading of large cross-section coniferous timber species. Holzforschung 66(3), 381-387. https://doi.org/10.1515/hf.2011.167

Asner, G.P, Knapp, D.E, Broadbent, E.N, Oliveira, P.J, Keller, M., Silva, J.N. 2005. Selective logging in the Brazilian Amazon. Science 310(5747):480-2. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1118051

Blanc, S., Lingua F., Bioglio L., Pensa R. G., Brun F., Mosso A. 2018. Implementing Participatory Processes in Forestry Training Using Social Network Analysis Techniques. Forests 9(8), 463. https://doi.org/10.3390/f9080463

Borgatti S.P., Cross R. 2003. A relational view of information seeking and learning in social networks. Management Science 49(4):432–445. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.49.4.432.14428

Carvalho, W.D., Mustin, K., Hilário, R.R., Vasconcelos, I.M., Eilers, V., Fearnside, P.M. 2019. Deforestation control in the Brazilian Amazon: A conservation struggle being lost as agreements and regulations are subverted and bypassed. Perspectives in Ecology and Conservation 17(3), 122-130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pecon.2019.06.002

CBD 2008. Biodiversity Glossary. Convention on Biological Diversity. https://www.cbd.int/cepa/toolkit/2008/doc/CBD-Toolkit-Glossaries.pdf. (Accessed: March 03, 2025).

Chazdon, R.L., Brancalion, P.H.S., Laestadius, L., Bennet-Curry, A., Buckingham, K., Mool-Rocek, J., Guimarães Viera, I.C., et al. 2016. When is a forest a forest? Forest concepts and definitions in the era of forest and landscape restoration. Ambio 45, 538–550. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-016-0772-y

Choi, B.C.K., Pang, T., Lin, V., Puska, P., Sherman, G., Goddard, M., et al. 2005. Can scientists and policy makers work together? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 59(8), 632–637. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2004.031765

CIFOR 2025. Glossary. Center for International Forestry Research. https://www.cifor-icraf.org/publications/pdf_files/Books/BAngelsen1801f.pdf. (Accessed: March 03, 2025).

CITES 2023. CITES glossary. The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. https://cites.org/eng/resources/terms/glossary.php#f. (Accessed: March 03, 2025).

CONAMA (Conselho Nacional Do Meio Ambiente). 2009. Resolução CONAMA n.º 406/2009. Estabelece parâmetros técnicos a serem adotados na elaboração, apresentação, avaliação técnica e execução de Plano de Manejo Florestal SustentávelPMFS com fins madeireiros, para florestas nativas e suas formas de sucessão no bioma Amazônia. Brasília, Brazil.

https://conama.mma.gov.br/?option=com_sisconama&task=arquivo.download&id=578

Condit, R., Hubbell, S. P., Foster, R. B. 1995. Demography and harvest potential of Latin American timber species: data from a large, permanent plot in Panama. Journal of Tropical Forest Science 7(4), 599–622. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43582459

Connif, R. 2017. Chasing the Illegal Loggers Looting the Amazon Forest. Wired, Oct, 24, 2017. https://www.wired.com/story/on-the-trail-of-the-amazonian-lumber-thieves/ (Accessed: April 24, 2025).

CPF 2025. Members of the Collaborative Partnership on Forests. Collaborative Partnership on Forests. https://www.fao.org/collaborative-partnership-on-forests/members/en. (Accessed: March 03, 2025).

d’Oliveira, M.V.N., Ribas, L.A. 2011. Forest regeneration in artificial gaps twelve years after canopy opening in Acre State Western Amazon. Forest Ecology and Management 261(11), 1722–1731. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2011.01.020

Daramola, G.O., Adewunmi, A., B., Jacks, B.S., Ajala, O.A. 2024. Navigating Complexities: A Review of Communication Barriers in Multinational Energy Projects. International Journal of Applied Research in Social Sciences 6(4), 685–697. https://doi.org/10.51594/ijarss.v6i4.1062

Dinerstein, E., Baccini,A., Anderson, M., Fiske, G., Wikramanayake, E., McLaughlin, D., et al. 2015. Guiding agricultural expansion to spare tropical forests: agricultural expansion in the tropics. Conservation Letters 8, 262-271, https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12149

Dobšinská, Z., Šálka, J., Urbančík, J. M., Sedmák, R., Bahýľ, J., Čerňava, J., Kropil, R. 2025. How can science solve forest management problems in urban forests? A case study of Bratislava Forest District. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening 104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2024.128630

Ducarme, F., Flipo, F., Couvet, D. 2021. How the diversity of human concepts of nature affects conservation of biodiversity. Conservation Biology 35(3), 1019-1028. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13639

Esperon-Rodriguez M. 2025. Trees, society, and the path toward resilient ecosystems. Plants People Planet in press. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppp3.10614

European Union 2023. 2023/1115 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 31 May 2023 on the making available on the Union market and the export from the Union of certain commodities and products associated with deforestation and forest degradation and repealing Regulation (EU) No 995/2010 (Text with EEA relevance). Official Journal of the European Union, L 150/206. Brussels, Belgium. http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2023/1115/oj

European Union. 2025. Commission guidance for the implementation of the EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR). Brussels, Belgium. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:C_202504524

Failing, L., Gregory, R. 2003. Ten common mistakes in designing biodiversity indicators for forest policy. Journal of environmental management 68(2), 121-132. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-4797(03)00014-8

FAO 2002. Expert Meeting on Harmonizing forest-related definitions for use by various stakeholders. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy, https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/d841ca8a-547a-41b1-bf2b-38895c0d0a54/content

FAO 2013. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations term portal. https://www.fao.org/forestry/46199/en/. (Accessed: November 26, 2023).

FAO 2018. Terms and definitions - FRA 2020. Forest Resources Assessment Working Paper 188. FAO Forestry Department. Rome, Italy. https://www.fao.org/3/I8661EN/i8661en.pdf

FAO 2020. REDD+ Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. https://www.fao.org/redd/news/detail/en/c/1318924/. (Accessed: March 03, 2025).

FAO 2025. FAO Terminology Portal. https://www.fao.org/faoterm/en/. (Accessed: March 03, 2025).

Ferrer Velasco, R., Köthke, M., Lippe, M., Günter, S. 2020. Scale and context dependency of deforestation drivers: Insights from spatial econometrics in the tropics. PLoS ONE 15(1): e0226830 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0226830.

Gandour C. 2001. Public Policies for the Protection of the Amazon Forest: What Works and How to Improve. Climate Policy Initiative. https://www.climatepolicyinitiative.org/publication/public-policies-for-the-protection-of-the-amazon-forest-what-works-and-how-to-improve/. (Accessed: March 03, 2025).

GCF 2025. Green Climate Fund. https://www.greenclimate.fund/. (Accessed: March 03, 2025).

GEF 2011. Glossary of Terms and Descriptions Relating to the Accreditation of GEF Project Agencies. Global Environment Facility. https://www.thegef.org/documents/glossary-terms-and-descriptions-relating-accreditation-gef-project-agencies. (Accessed: March 03, 2025).

Geldenhuys, C.J. 2010. Managing forest complexity through application of disturbance-recovery knowledge in development of silvicultural systems and ecological rehabilitation in natural forest systems in Africa. Journal of Forest Research 15(1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10310-009-0159-z

GFC (Guyana Forestry Commission). 2018. Code of Practice for Forest Operations. Georgetown, Guyana. https://forestry.gov.gy/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/CoP-for-Forest-Operations-2018.pdf

Gobierno de Colombia 2020. Plan de acción del pacto de Leticia. Cancillería de Colombia. Bogotá, Colombia. https://www.cancilleria.gov.co/sites/default/files/plandeaccionpactodeleticiaporlaamazonia.pdf

Guimarães Vieira, I.C., Gardenr T., Ferreira, J., Lees, A.C., Barlow, J. 2014. Challenges of governing second-growth forests: a case study from the Brazilian Amazonian state of Pará. Forests 5, 1737-1752. https://doi.org/10.3390/f5071737

Gunatilleke, N. 2015. Forest sector in a green economy: A paradigm shift in global trends and national planning in Sri Lanka. Journal of the National Science Foundation of Sri Lanka 43(2), 101–109. https://doi.org/10.4038/jnsfsr.v43i2.7937

Harde-Wolfson, E, Quinteiro, J.A. 2024. Public goods, common goods and global common goods: A brief explanation. UNESCO International Institute for Higher Education in Latin America and the Caribbean. https://www.iesalc.unesco.org/en/articles/public-goods-common-goods-and-global-common-goods-brief-explanation (Accessed: June 10, 2025).

Hariram, N.P., Mekha, K.B., Suganthan, V., Sudhakar, K. 2023. Sustainalism: An Integrated Socio-Economic-Environmental Model to Address Sustainable Development and Sustainability. Sustainability 15(13), 10682. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310682

Hein, S. 2009. Appendix A: Definition of Valuable Broadleaved Forests in Europe. In: Spiecker, H., Hein, S., Makkonen-Spiecker, K., Thies, M. (eds). Valuable Broadleaved Forests in Europe, EFI Research Report 22. Brill: Leiden, Boston, Köln, Germany.

Helms, J.A. 2002. Forest, forestry, forester: What do these terms mean? Journal of Forestry 100(8), 15-19. https://doi.org/10.1093/jof/100.8.15

Herrera-Alvarez, X. 2024. A Modern Approach To The Concept Of Timber Species From An Amazonian Perspective. PhD Thesis, Public University of Navarre. Pamplona, Spain. https://doi.org/10.48035/Tesis/2454/52801

Hwang, K. 2013. Effects of the Language Barrier on Processes and Performance of International Scientific Collaboration, Collaborators’ Participation, Organizational Integrity, and Interorganizational Relationships. Science Communication 35(1), 3-31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547012437442

IBAMA (Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais Renováveis). 2022. Instrução Normativa IBAMA n.º 16/2022. Sistema Documento de Origem Florestal (DOF+). Brasília, Brazil. https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/instrucao-normativa-n-16-de-25-de-novembro-de-2022-448030474

INPARQUES (Instituto Nacional de Parques). 2019. Sistema de guías electrónicas para productos forestales maderables. Caracas, Venezuela.

ITTO 2009. Handbook. International Timber Trade Organization. Yokohama, Japan. https://www.itto.int/files/user/pdf/publications/General%20Information/ITTO%20Handbook%20(CFA24-7).pdf

ITTO 2012. Appendix 3: Major tropical species traded in 2010 and 2011. In: Annual review and assessment of the world timber situation 2012. International Timber Trade Organization. Yokohama, Japan. Avilable at: https://www.itto.int/biennal_review/

ITTO 2013. The ITTO statistical system: From the JFSQ to the annual review. International Timber Trade Organization. https://www.itto.int/files/user/presentations/The ITTO Statistical System.pdf . Yokohama, Japan. (Accessed: June 10, 2025).

ITTO 2021. Annual report 2020. International Tropical Timber Organization, Yokohama, Japan. https://www.itto.int/direct/topics/topics_pdf_download/topics_id=6775&no=1

IUCN 2022. International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). https://iucn.org/sites/default/files/2022-06/iucn-glossary-of-translated-terms-en-es-fr.pdf. (Accessed: March 03, 2025).

IUFRO 2024. International Union of Forest Research Organizations. https://www.iufro.org/science/special/silvavoc/silvaterm/query-silvaterm-database/. (Accessed: March 03, 2025).

Jones, N.H., Walsh, C. 2008. Policy briefs as a communication tool for development research. Overseas Development Institute. London. https://odi.org/documents/1217/594.pdf

Jones, N., Jones, H., Walsh, C. 2008. Political science? Strengthening science – policy dialogue in developing countries. Overseas Development Institute. London. https://odi.org/documents/1170/474.pdf

Karsenty, A., Gourlet-Fleury, S. 2006. Assessing sustainability of logging practices in the Congo Basin’s managed forests: The issue of commercial species recovery. Ecology and Society 11(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-01668-110126

Keating, W.G. 1980. Utilization of mixed species through grouping and standards. Australian Forestry 43(4), 233–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049158.1980.10674277

Kennard, D.K., Putz, F.E. 2005. Differential responses of Bolivian timber species to prescribed fire and other gap treatments. New Forests 30(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11056-004-0762-y

Leach, M., Fairhead, J. 2025. Changing Perspectives on Forests: Science/Policy Processes in Wider Society. IDS Bulletin 56.1A: 50–61. https://doi.org/10.19088/1968-2025.108

Lima, F.B.D., Souza, Á.N.D., Matricardi, E.A.T., Gaspar, R.d.O., Lima, I.B.D., Souza, H.J.D., et al. 2024. Alternative Tree Species for Sustainable Forest Management in the Brazilian Amazon. Forests 15, 1763. https://doi.org/10.3390/f15101763

López-Tobar, R, Herrera-Feijoo, RJ, García-Robredo, F, Mateo, RG, Torres, B. 2024. Timber harvesting and conservation status of forest species in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Frontiers in Forests and Global Change 7:1389852. https://doi.org/10.3389/ffgc.2024.1389852

Lund, H.G. 2002. When is a forest not a forest? Journal of Forestry 100(8), 21-28. https://doi.org/10.1093/jof/100.8.21

MAATE & MAG (Ministerio de Ambiente, Agua y Transición Ecológica & Ministerio de Agricultura y Ganadería). 2022. Acuerdo Interministerial Nro. MAATE-MAG-2022-003 - Norma Técnica para la emisión del Certificado de Procedencia Legal y Buenas Prácticas Forestales de Productos Maderables y No Maderables. Registro Oficial - Tercer Suplemento Nº 177. Quito, Ecuador.

MacLeod, M. 2018. What makes interdisciplinarity difficult? Some consequences of domain specificity in interdisciplinary practice. Synthese 195, 697–720. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-016-1236-4

McNeal, D.M., Glasgow, R.E., Brownson, R.C., Matlock, D.D., Peterson, P.N., Daugherty, S.L., Knoepke, C.E. 2020. Perspectives of scientists on disseminating research findings to non-research audiences. Journal of Clinical and Translational Science 5(1):e61. https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2020.563

MinAmbiente (Ministerio de Medio Ambiente). 2015. Decreto Único Reglamentario 1076 de 2015 Sector Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible. Bogotá, Colombia. https://www.minambiente.gov.co/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Decreto-1076-de-2015.pdf

MinAmbiente (Ministerio de Medio Ambiente). 2017. Resolución 1909 de 2017, por la cual se establece un Salvoconducto Único Nacional en Línea para la movilización de especímenes de la diversidad biológica (SUNL). Bogotá, Colombia. https://www.minambiente.gov.co/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/resolucion-1909-de-2017.pdf

MINAGRI (Ministerio de Agricultura). 2015. Decreto Supremo 018-2015-MINAGRI. Reglamento para la Gestión Forestal. Lima, Perú. https://sinia.minam.gob.pe/sites/default/files/sinia/archivos/public/docs/ds18-2015-minagri.pdf

MMA (Ministério do Meio Ambiente). 2006. Instrução Normativa n.º 5/2006. Procedimentos técnicos para elaboração, apresentação, execução e avaliação técnica de Planos de Manejo Florestal Sustentável-PMFSs nas florestas primitivas e suas formas de sucessão na Amazônia Legal. Brasília, Brazil. https://snif.florestal.gov.br/images/pdf/legislacao/normativas/in_mma_05_2006.pdf

Murphy, C.W, Pellaton P., Fuller, S. 2022. Improving the Transfer of Knowledge from Scientists to Policy Makers: Best Practices and New Opportunities to Engage. National Center for Sustainable Transportation. University of California, Davis. http://dx.doi.org/10.7922/G2J101G9

Muthoni, G.S. 2002. ‘Factors Influencing Good Governance in Forest Management and Protection: A Case Study of Mt. Elgon Forest Reserve, Kenya’. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development 11(12), 42–47. http://dx.doi.org/10.7176/jesd/11-12-06

ONF (Office National des Forêts). 2023. Règlement d’exploitation forestière en Guyane. Cayenne, Guyane française. https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/codes/section_lc/JORFTEXT000000485639/LEGISCTA000006122057/#LEGISCTA000006122057 [accessed November 17th, 2025]

OTCA 2019. Evaluación sobre la gestión forestal sustentable y conservación de la biodiversidad en la Amazonía. Sistematización de resultados de los informes nacionales de los Países miembros de la OTCA. Organización del Tratado de Cooperación Amazónica. Brasilia, Brazil. https://otca.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Sistematizacion-de-Resultados-de-los-Informes-Nacionales-de-los-Paises-Miembros-de-la-OTCA.pdf

Oum Lissouck, R., Pommier, R., Breysse, D., Ayina Ohandja, L. M., Dong A Mansié, R. 2016. Clustering for preservation of endangered timber species from the Congo Basin Forest. Journal of Tropical Forest Science 28(1), 4–20. https://jtfs.frim.gov.my/jtfs/article/view/537

Ozga, J. 2004. From Research to Policy and Practice: Some Issues in Knowledge Transfer. CES Briefing No.31, University of Edinburgh, 31, 4. https://www.ces.ed.ac.uk/PDF%20Files/Brief031.pdf

Page, M.J., McKenzie, J.E., Bossuyt, P.M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T.C., Mulrow, C.D., et al. 2021. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372, 71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Pan, Y., Birdsey, R.B., Fang J.Y., Houghton R., Kauppi P.E., Kurz W.A. et al. 2011. A Large and Persistent Carbon Sink in the World’s Forests. Science 333, 988-993. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1201609

Pan, Y., Birdsey, R.A., Phillips, O.L., Jackson, R.B. 2013. The structure, distribution, and biomass of the world’s forests. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 44, 593–622. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110512-135914

PEFC (Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification). 2025. Standard PEFC pour la gestion forestière durable en Guyane. Paris, France. https://www.pefc-france.org/wp-content/uploads/PEFC_FR-ST-1003-2_2025_Gestion-forestiere-durable-Exigences-pour-la-Guyane-Francaise.pdf

Pitman N., Terborgh J.W., Silman M.R., Nuñez V.P., Neill D.A., Cerón C.E., Palacios W. 2001. Dominance and distribution of tree species in upper Amazonian terra firme forests. Ecology 84, 2101–2117. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-96582001)082[2101:DADOTS]2.0.CO;2

Ptichnikov, A.V., Martynyuk, A.A. 2020. Adaptation of International Indicators of Land Degradation Neutrality for the Assessment of Forest Ecosystems in Arid Conditions in Russia. Arid Ecosystems 10(2), 127–134. https://doi.org/10.1134/S2079096120020109

Pulido-Salgado, M., Castaneda Mena, F.A. 2021. Bringing Policymakers to Science Through Communication: A Perspective from Latin America. Frontiers in Research Metrics and Analytics 6(April), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3389/frma.2021.654191

Racelis, A., Barsimantov, J. 2013. Rethinking the Role of Tropical Forest Science in Forest Conservation and Management. In: Lowman, M., Devy, S., Ganesh, T. (eds) Treetops at Risk, pp 81-91. Springer, New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-7161-5_6

Ramirez, L.F., Belcher, B.M. 2019. Stakeholder perceptions of scientific knowledge in policy processes: A Peruvian case-study of forestry policy development. Science and Public Policy 46(4), 504–517. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scz003

República Bolivariana de Venezuela. 2013. Ley de Bosques. Gaceta Oficial de la República Bolivariana de Venezuela, Nº 40.222. Caracas, Venezuela.

República de Bolivia. 1996. Ley Forestal 1700, 12 de julio de 1996. BO 09.008.0044. La Paz, Bolivia.

Republic of Suriname. 1992. Forest Management Act (Wet Bosbeheer 1992). Oficial Gazette of the Republic of Suriname, 1992, 80.

République Française. 2023. Code forestier – dispositions particulières à l’outre-mer (Guyane). Paris, France. https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/codes/section_lc/LEGITEXT000025244092/LEGISCTA000025247428/. [Accessed on November 17th, 2025].

Richards, A.E., Schmidt, S. 2010. Complementary resource use by tree species in a rain forest tree plantation. Ecological Applications 20(5), 1237–1254. https://doi.org/10.1890/09-1180.1

Rohana, H., Azmi, I., Zakiah, A. 2010. Shear and bending performance of mortise and tenon connection fastened with dowel. Journal of Tropical Forest Science 22(4), 425–432. https://jtfs.frim.gov.my/jtfs/article/view/984

Ruseva, T.B., Evans, T.P., Fischer, B.C 2014. Variations in the social networks of forest owners: the effect of management activity, resource professionals, and ownership size. Small-scale Forestry 13, 377-395. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11842-014-9260-z.

Samanez-Mercado R. 1990. Le Défi amazonien. Unasylva 163, 22-27. Available at: https://www.fao.org/4/u0700f/u0700f06.htm#le%20d%C3%A9fi%20amazonien

SBB (Stichting Bosbeheer en Bostoezicht). 2011. Code of Practice for Forest Operations in Suriname. Paramaribo, Suriname. https://www.tropenbos.org/app/data/uploads/sites/2/CoP-infosheet-1.pdf

Schöngart, J. 2008. Growth-Oriented Logging (GOL): A new concept towards sustainable forest management in Central Amazonian várzea floodplains. Forest Ecology and Management 256(1–2), 46– 58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2008.03.037

Schulze, M., Grogan, J., Landis, R. M., Vidal, E. 2008. How rare is too rare to harvest? Management challenges posed by timber species occurring at low densities in the Brazilian Amazon. Forest Ecology and Management 256(7), 1443–1457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2008.02.051

SERFOR (Servicio Nacional Forestal y de Fauna Silvestre). 2023. Resolución de Dirección Ejecutiva N.° D0000163-2023-MIDAGRI-SERFOR-GG. Lista Oficial de Especies Forestales. Lima, Perú. https://www.gob.pe/institucion/serfor/normas-legales/4444921-d0000163-2023-midagri-serfor-gg

SERFOR (Servicio Nacional Forestal y de Fauna Silvestre). 2024. Resolución de Dirección Ejecutiva N.° D000014-2024-MIDAGRI-SERFOR-DE. Formato oficial de la Guía de Transporte Forestal (GTF). Lima, Perú. https://www.gob.pe/institucion/serfor/normas-legales/5042229-d000014-2024-midagri-serfor-de

The Science Panel for the Amazon 2021. The Amazon we want. Available at: https://www.sp-amazon.org/ (Accessed: June 10 2025).

SDSN 2023. Science Panel for the Congo Basin. UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network. https://www.unsdsn.org/our-work/science-panel-for-the-congo-basin/ (Accessed: June 10, 2025).

Sienkiewicz, M., Mair, D. 2020. Against the Science–Policy Binary Separation. In Sucha V, Sienkiewiecz M. Science for Policy Handbook pp 2-13. Elsevier, Amsterdam. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-822596-7.00001-2

Spiecker, H., Hein, S., Makkonen-Spiecker, K., Thies, M. (eds.) 2010. Valuable Broadleaved Forests in Europe. EFI Research Report 22. Brill: Leiden, Boston, Köln. https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004167957.i-256.

Steele, R., Cooper, S.V., Ondov, D.M., Roberts, D.W., Pfister, R.D. 1983. Forest habitat types of eastern Idaho-western Wyoming. General Technical Report - US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service (Issue INT-144). https://www.fs.usda.gov/rm/pubs_series/int/gtr/int_gtr144.pdf

Suaa, C., Owusu, J., Aboagye, K.O., Donkor, M., Boateng, P.A., Owusu-yeboah, E. 2024. The impact of language differences on effective communication in multinational corporations in Ghana. IOSR Journal of Business and Management 26(12), 45–54. https://doi.org/10.9790/487X-2612014554

Teel, W.S., Lassoie, J.P. 1991. Woodland management and agroforestry potential among dairy farmers in Lewis County, New York. The Forestry Chronicle 67(3), 236–242. https://doi.org/10.5558/tfc67236-3

The World Bank. 1996. The World Bank glossary: English - Spanish. Washington DC, USA. ISBN 0-8213-3595-2. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/541831468326979631/pdf/322800PUB00PUB0d0bank0glossary01996.pdf

Theokritoff, E. 2018. Linking science and policy for climate change adaptation: The case of Burkina Faso A stocktaking of the integration of scientific information on climate change into national. KTH Royal Institute of Technology. Stockholm, Sweden. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1271334/FULLTEXT01.pdf

UNCCD 2025. UNCCD Terminology. United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification. https://www.unccd.int/data-knowledge/unccd-terminology. (Accessed: March 03, 2025).

UNDESA 2025. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/. (Accessed: March 03, 2025).

UNDP 2025. Glossary. Programme and Operations Policies and Procedures. United Nations Development Programme. https://popp.undp.org/glossary. (Accessed: March 03, 2025).

UNEP 2025. UNEP GEO Glossary. United Nations Environment Programme. https://wesr-staging.azurewebsites.net/glossary/. (Accessed: March 03, 2025).

UNFCCC 2025. Glossary. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. https://unfccc.int/resource/cd_roms/na1/ghg_inventories/english/8_glossary/Glossary.htm#T. (Accessed: March 03, 2025).

United Nations 2007. Collaborative Partnership on Forests Framework 2007. United Nations Forum on Forests, Seventh session. 23064 (February), 1–16. Economic and Social Council. United Nations. https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/n07/230/64/pdf/n0723064.pdf.

Vaca, R.A., Golicher, D.J., Macario-Mendoza, P.A., Estrada-Lugo, E.I.J., Bello-Baltazar, E., Sánchez- Pérez, L.C., Shanahan, M.J. 2022. Site Quality for Mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla King) in Natural Forests in Quintana Roo. Journal of Sustainable Forestry 41(1), 33–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/10549811.2020.1841004

Washbourne, C.L., Murali, R., Saidi, N., Peter, S., Pisa, P.F., Sarzynski, T., Ryu, H., et al. 2024. Navigating the science policy interface: a co-created mind-map to support early career research contributions to policy-relevant evidence. Environmental Evidence 13(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13750-024-00334-5

World Agroforestry 2018. Tree improvement glossary, Illustrated glossary of terms used in forest tree improvement. Technical Note N0. 46. https://www.worldagroforestry.org/output/tree-improvement-glossary. (Accessed: March 03, 2025).

Zafra-Calvo, N., Ortega, U., Sertutxa, U., Moreaux, C. 2024. Identifying key actors, barriers and opportunities to lead a transition towards sustainable forest management: an application to the Basque Country, Spain. Trees, Forest and People 18, 100727. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tfp.2024.100727

Zalles, V., Harris, N., Stolle, AHnse, M. 2024. Forest definitions require a re-think. Communications Earth and Environment 5, 620. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01779-9

Appendix / Anexo. Supporting Information

1. Exclusion Criteria

1.1. Non-relevant topics excluded in the Web of Science database

Literature in Polish, Croatian, Malay, French, Spanish, Japanese, Russian, German, Lithuanian, Turkish, Portuguese and unspecified languages was not included. Literature that was not related to the target topic was also excluded, such as: Pharmacology, Pharmacy, Geochemistry, Geophysics, Social Sciences, Geology, Integrative Complementary Medicine, Mycology, Business Economics, Water Resources, Oncology, Behavioral Sciences, Physical Geography, Biotechnology Applied Microbiology, Physical Sciences, Science Technology, Chemistry, Reproductive Biology, Mathematical Computational Biology, Computer Science, Immunology, Mathematics, Developmental Biology, Mechanics, Life Sciences Biomedicine, Fisheries, Neurosciences, Neurology, Zoology, Microbiology, Optics, Engineering, Nutrition Dietetics, Veterinary Sciences, Meteorology Atmospheric Sciences, Pathology, Acoustics, Public Administration, Physiology, Geography, Infectious Diseases, Area Studies, Evolutionary Biology, International Relations, Art, Genetics Heredity, Public Environmental Occupational Health, Arts, Humanities, Psychology, Archaeology, Development Studies, Biochemistry Molecular, Biology, Cell Biology, Education, Educational Research, Government Law, History, Endocrinology Metabolism, Paleontology, Geriatrics, Gerontology, Marine Freshwater Biology, Remote Sensing, Physics, Anthropology, Sociology, Radiology Nuclear Medicine, Medical Imaging, Toxicology, Automation Control Systems, Robotics, Anatomy Morphology, Communication, Spectroscopy, Food Science Technology, Entomology, Telecommunications, Instruments Instrumentation, Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Urban Studies.

1.2. Non-relevant topics excluded in the Scopus database