Introduction

Scleria

P.J.Bergius (1765: 142), commonly known as nut rushes or razor grasses, is the

sixth largest genus in the Cyperaceae family with around 260 species (Bauters et al.

2016; Larridon et al. 2021;

2024), and the only genus of tribe Sclerieae Wight & Arn. (subfamily

Cyperoideae) (Larridon 2022). Scleria has four subgenera and 17

sections (Bauters

et al. 2016, 2018a, 2019). Most

species occur in tropical areas but some occupy more temperate climatic regions

(Larridon et

al. 2021). Scleria

is a functionally diverse genus that includes annual and perennial herbs, the

latter often using stoloniferous rhizomes or tubers (Bauters

et al. 2016; Galán Díaz et al. 2019). Nut

rushes are ecologically important in wetlands and areas undergoing secondary

succession (Bauters et al. 2016), and some

species are reported to have local economic significance (Simpson y Inglis 2001; Galán Díaz et

al. 2024).Recent studies have disentangled the

evolutionary relationships among Scleria species (Bauters et al. 2016, 2018) and identified major dispersal and niche

shift events (Larridon et

al. 2021). Still, we lack a

global assessment of species and world regions of remarkable interest for Scleria

conservation.

In the current context of rapid global

change, there is a need to adopt new tools to assess biodiversity and

ecosystems to set conservation priorities (Cowell

et al. 2022). Over the

last two decades, the use of phylogenetic and functional indices has emerged as

a powerful approach to support conservation assessments by identifying at-risk

species and regions of great evolutionary and ecological uniqueness (Kondratyeva

et al. 2019). The

Evolutionarily Distinct and Globally Endangered (EDGE) metric can be used to

rank species conservation priorities where species’ evolutionary

distinctiveness (ED) is used as a surrogate of their irreplaceability, and

species’ probability of extinction (GE) is used as a proxy of their

vulnerability (Isaac et al.

2007). It has been

successfully implemented in different groups such as corals (Huang 2012), mammals and amphibians (Safi et al.

2013), gymnosperms (Forest

et al. 2018) and

tetrapods (Gumbs et al.

2018). The EDGE metric has

been recently revised to include new advances (EDGE2; Gumbs et

al. 2023): (i) species’

evolutionary distinctiveness (ED2) now considers the extinction risk of their

close relatives; (ii) it allows the incorporation of uncertainty in the

phylogeny and extinction risk. The latter allows the use of phylogenies which

have been expanded using non-molecular information (e.g., see Ramos-Gutiérrez et al. 2023), and provides a flexible framework to assess Not Evaluated and

preliminary assessed species rather than only depending on species published in

the Red List of Threatened Species of the International Union for Conservation

of Nature (IUCN) (e.g., Walker et

al. 2023).

Machine learning approaches constitute

efficient tools to produce extinction risk assessments and their implementation

in different plant groups has provided promising results (Zizka et al.

2022; Bachman et al. 2023; Walker et al. 2023). The latest version of the Red List

includes ~18% (62 666 species) of all known vascular plant species (IUCN 2023). In the case of Scleria, there are

extinction risk assessments available for 183 species (26 of which are not yet

publicly available in the latest version of the Red List), which accounts for

70% of the genus. Recent taxonomic revisions of the genus (Bauters

et al. 2016, 2018a, 2019; Galán Díaz et al. 2019) and the availability of occurrence

datasets curated using expert knowledge (Larridon et

al. 2021) can help overcome

some of the limitations and challenges that arise from using herbarium

collections to support preliminary extinction risk assessments (Nic Lughadha

et al. 2019). The

genus Scleria is therefore a good study system to train machine learning

algorithms and produce preliminary extinction risk assessments.

Finally, the phylogenetic and functional

components of biodiversity are not necessarily correlated, especially when

considering functional attributes which are highly dependent on the environment

(Losos 2008). Scleria is an ecologically diverse

clade that includes species with variable habits, from tiny annuals with small

nutlets and fibrous roots to climbers or stout perennials with big buoyant

propagules (Galán Díaz

et al. 2019). The

variation in functional traits across the genus Scleria therefore

warrants independent evaluation. In this regard, the EDGE2 framework can

incorporate species functional distinctiveness (FUD) as a measure of ecological

irreplaceability. This metric is termed Ecologically Distinct and Globally

Endangered (EcoDGE) (Hidasi-Neto et al. 2015).

Here, (i) we first produced preliminary

extinction risk assessments for the ~30% of Scleria species that do not

yet have a global Red List assessment, and then (ii) followed the EDGE2

protocol to identify evolutionary and ecologically distinct Scleria

species at greatest risk of extinction and conservation priority areas. For

this, we used extinction risk assessments from the global Red List and the most

comprehensive phylogeny of Scleria to date (Larridon et

al. 2021), as well as newly

compiled occurrence and traits datasets.

Material and Methods

Taxonomy and species occurrences

We used the World Checklist of Vascular

Plants (WCVP; Govaerts

et al. 2021) and the latest

taxonomic revisions of the genus Scleria P.J.Bergius (Bauters

et al. 2016, 2019) to compile

a dataset of 261 accepted species. Data relating to infraspecific taxa were

incorporated at the species level. Species names and authorities are available

in in Table A1 of Appendix.

Occurrence data was compiled using

observations from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF 2023), Red List (IUCN 2023), research-grade identifications from iNaturalist and

records for collections from BR, K, GENT, L, MO, NY, P, US and WAG which were

georeferenced using Google Earth. For each species, we filtered observations

following several steps: (1) we removed duplicates and retained one observation

per 1km2 raster cell, (2) filtered observations based on the native

ranges at the ‘botanical country’ scale, according to the WCVP, and (3)

excluded observations 1.5 times outside the interquartile climatic range using

the mean annual temperature and annual precipitation BIOCLIM variables (Booth et al.

2014). The final occurrence

database included 22 759 observations from 248 species. We projected locality

data using the Equal Earth map projection (Šavrič

et al. 2019).

Traits measurements and

calculation

We measured maximum height, maximum blade

length, maximum blade width, nutlet length and nutlet width from 1254 specimens

housed at Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew (K) and the Muséum National d'Histoire

Naturelle in Paris (P). For species missing in these herbaria, we completed the

dataset using information from protologues and descriptions from regional

floras (e.g., Davidse et al. 1994; Simpson and

Koyama 1998; Le Roux 2015).

This information was used to estimate three traits informative of plant

ecological strategies (Westoby 1998): maximum height (i.e., distance from the

top inflorescence to the ground), leaf area and size of the propagule (i.e.,

nutlet volume). We estimated leaf area and nutlet volume using the formula of

an ellipse and an ellipsoid, respectively. We also considered plant longevity

(annual/perennial).

Extinction risk data and

preliminary assessments

Previous studies have shown that the Red

List is biased toward certain plant groups and species, for instance, woody

perennials and useful plants (Nic Lughadha et al. 2020). Still, we

used the Red List categories as indicators of species’ extinction risk because

(i) the Red List constitutes a consensual framework worldwide, (ii) the authors

have been continuously involved in the production of several Red List

assessments of Scleria over the last decade which facilitates the

interpretation of the results, (ii) Scleria is nearly comprehensively

assessed according to the Red List criterium (i.e., taxa with over 149 species

with at least 80% of the species assessed) and (iv) recent advances in the EDGE

protocol used Red List categories as proxies of species’ probability of

extinction (Gumbs et al. 2023)

We downloaded 157 extinction risk

assessments from the Red List (version 2023-1) and considered the extinction

risk category of other 26 species that have assessments in preparation. To

supplement the 183 species with global (published and in preparation) Red List

assessments we carried out preliminary assessments and predictions for the 67

Data Deficient (DD) and Not Evaluated (NE) species for which occurrence data

was available so that we had an extinction risk assessment for all species. The

extinct species S. chevalieri J.Raynal was excluded from the analyses.

We followed two approaches:

·

We estimated species extinction risk categories

under IUCN Red List criterion B using the function ‘ConBatch’ from the R

package ‘rCAT’ (Moat & Bachman

2020). Given a dataset of occurrences, this function provides preliminary

extinction risk categories based on species’ extent of occurrence (EOO). We did

not consider the species' area of occupancy (AOO) because it can lead to an

overestimation of extinction risk when using occurrence data derived from

herbarium records (Nic Lughadha

et al. 2019). To

assess the accuracy of this method, we ran ‘ConBatch’ on the species included

in the Red List and compared the actual assessments with the predicted

categories.

·

We implemented a machine learning algorithm

(random forest, henceforth RF) using as predictors: EOO, AOO, mean of

latitudinal range, elevation, minimum human population density in 2020 (HPD; CIESIN 2016),

human footprint index in 2013 (HFI; Mu et a. 2022), proportion of

observations located in protected areas (UNEP-WCMC y

IUCN 2023), mean annual

temperature, minimum temperature of the coldest month, temperature annual

range, annual precipitation, precipitation of the driest month and

precipitation seasonality. All predictors were resampled at 30 seconds. For HPD

and HFI, we calculated the average index value within a 5 km circular buffer of

each unique occurrence point. We used 10 repeats of 5-fold cross-validation to

train and evaluate the model and retained 20% of data for external validation.

EDGE2 and EcoDGE calculation and

species lists

We computed two metrics that combine

species extinction risk with their evolutionary or functional distinctiveness

to prioritize at-risk Scleria species and world regions of special

interest for conservation: the Evolutionarily Distinct and Globally Endangered

metric (EDGE2) (Gumbs et al.

2023) and the Ecologically

Distinct and Globally Endangered metric (EcoDGE) (Hidasi-Neto et al. 2015). To compute ED2, we used the latest

phylogenetic inference of the genus from Larridon et al. (2021b), which included

136 species. We used the R package ‘randtip’ (Ramos-Gutiérrez

et al. 2023) to impute 111 species missing in

the phylogeny but for which infrageneric information (i.e., section) was

available. We excluded 14 species for which infrageneric information was not

available. Trees were expanded following several criteria: species were imputed

in their sections at random, the probability of branch selection was set as

equiprobable, and the stem branch was considered as a candidate for binding.

This step was repeated to generate a distribution of 500 randomly imputed

phylogenetic trees.

To calculate FUD, we adapted the EcoDGE

framework proposed by Hidasi-Neto et al. (2015) to the new

EDGE2 protocol following Griffith

et al. (2022). We generated a dendrogram by

calculating pairwise species dissimilarities with a generalized Gower's

distance matrix (Gower 1971) using the four traits (i.e., longevity,

maximum height, leaf area and size of the propagule) and an unweighted pair

group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA). We repeated the dendrogram

construction 11 times (all possible combinations of two, three and four traits)

to reduce the impact of specific traits on the results. Finally, we multiplied

FUD scores by 100 to balance the weighting of the two component values of the

EcoDGE metric.

The EDGE2 and EcoDGE protocols allow the

incorporation of uncertainty in the quantification of extinction probabilities

by associating each Red List category to a distribution of extinction

probabilities based on a 50-year time horizon (Mooers et al. 2008). For species not included in the Red List and classified as

threatened by the preliminary assessments, the extinction risk component

(GE) was randomly drawn from CR, VU and EN categories. For species classified

as non-threatened, GE values were randomly withdrawn from those of NT and LC

categories.

Finally, for each species, we calculated a

distribution of EDGE2 and EcoDGE scores (N=500) which were used to sort Scleria

species in three lists as proposed by Gumbs et al. (2023): a ‘priority or main

EDGE2 species list’ that includes threatened species whose distribution of

EDGE2 scores rank above the median of the entire genus at least 95% of the

times; a ‘borderline EDGE2 species list’ that includes threatened species whose

distribution of EDGE2 scores rank above the median of the entire genus at least

80% of the times; and a ‘watch EDGE2 species list’ that includes nonthreatened

species whose distribution of EDGE2 scores rank above the median of the entire

genus at least 95% of the times. We further discuss the results in the context

of the countries and world terrestrial ecoregions (Olson et al.

2001), which are good

descriptors of plant distribution (Smith et al.

2018) and can be used as

informative units for conservation planning (Dinerstein

et al. 2017).

All analyses were performed in R (version

4.3.2).

Results

Preliminary assessments

rCAT and RF yielded different results (Table A2 of Appendix). Under criterion B, rCAT classified 53 out of the 67 non-assessed

species as threatened according to their EOO (44 CR, 5 EN, 4 VU, 4 NT, 10 LC). Scleria

rCAT assessments correctly classified 79.31% of threatened species (high

sensitivity) and 91.39% of non-threatened species (high specificity). RF

classified 39 species as threatened and 28 as non-threatened. It achieved an

accuracy of 97.22%, correctly classifying 96.55% of non-threatened species and

all threatened species (higher sensitivity and specificity than rCAT). The

single most important predictor for RF was EOO, followed by AOO. Because of its

greater performance, we retained the results of RF for the EDGE2 and EcoDGE

calculations. Combined Red List results (published, unpublished and

preliminary) are available in Table

A1 of Appendix.

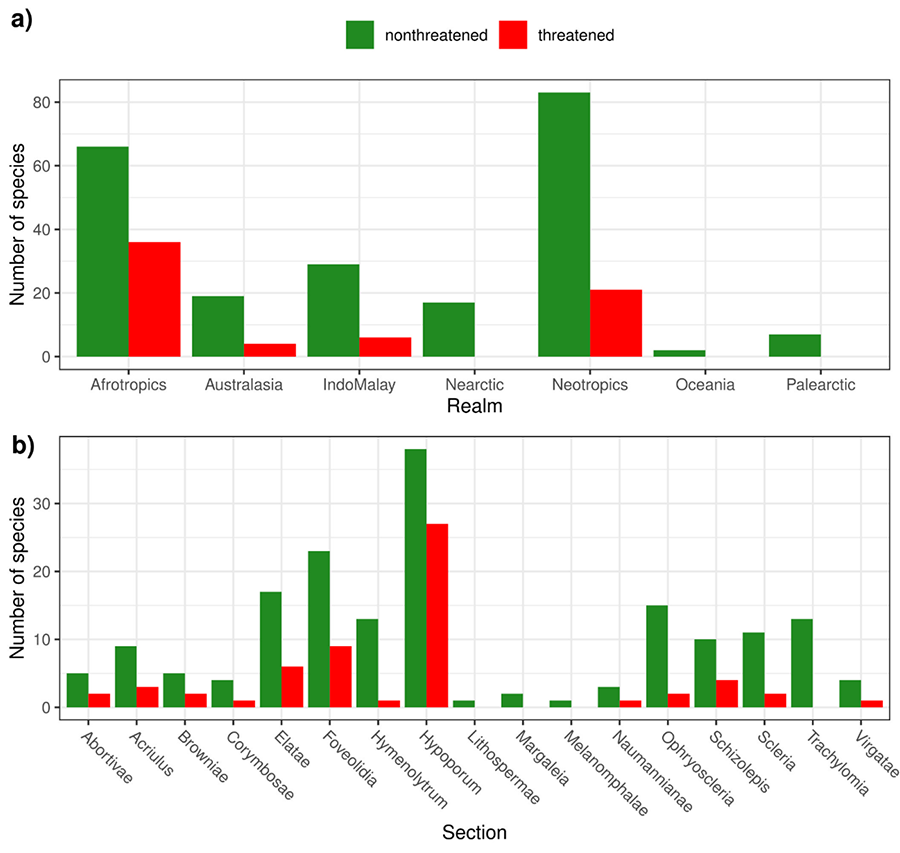

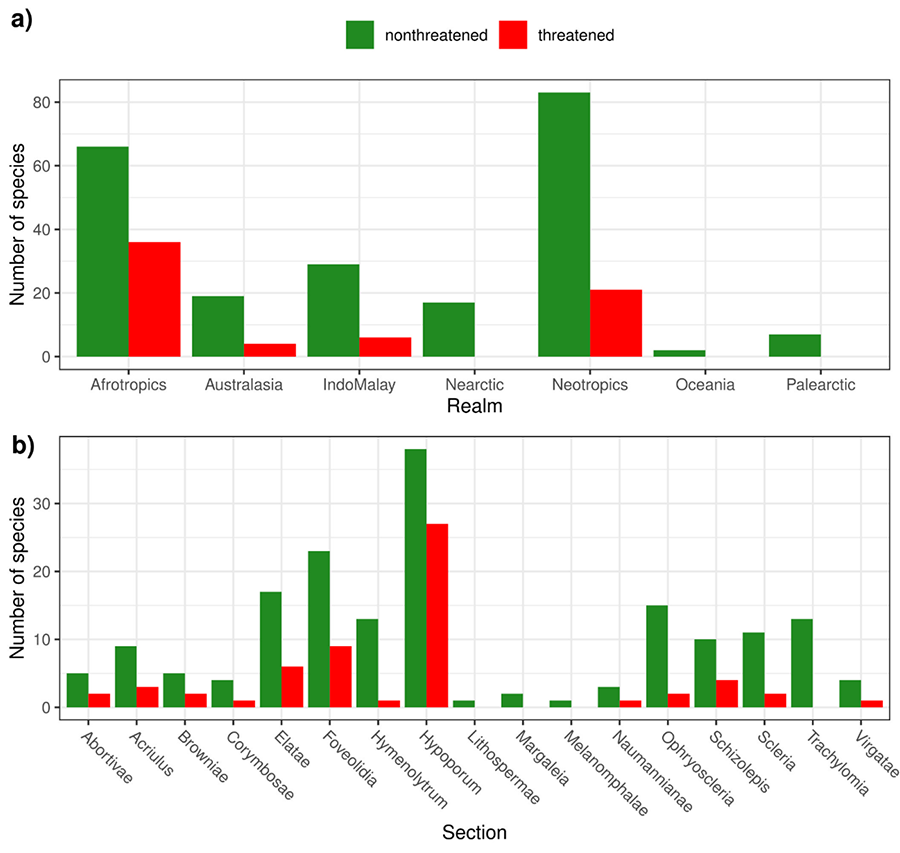

Considering

the published (Red List version 2023-1; IUCN 2023) and preliminary (RF) results,

we found that the Afrotropics and the Neotropics had the highest number and

proportion of threatened species (Fig. 1a). The sections with the

greatest proportion of threatened species were Hypoporum (41.54%),

followed by Abortivae, Browniae, Schizolepsis and Foveolidia (28.57%) (Fig. 1b).

Figure 1. Number of threatened and non-threatened Scleria species

grouped by (a) Realm (Olson et al.

2001) and (b)

Section. Threatened refers to species classified as Vulnerable (VU), Endangered

(EN) and Critically Endangered (CR) in the Red List, as well as Data Deficient

(DD) and Not Evaluated (NE) species classified as threatened by the random

forest approach. Non-threatened refers to species classified as Least Concern

(LC) and Near Threatened (NT) in the Red List, as well as Data Deficient (DD)

and Not Evaluated (NE) species classified as non-threatened by the random

forest approach.

Figura 1. Número de especies de Scleria

amenazadas y no amenazadas agrupadas por (a) Reino biogeográfico (Olson et al. 2001) y (b) Sección. Amenazadas

agrupa especies clasificadas como Vulnerable (VU), En Peligro (EN) y En Peligro

Crítico (CR) en la Lista Roja, así como especies en las categorías No Evaluado

(NE) y Datos Insuficientes (DD) clasificadas como amenazadas por el random forest.

No amenazadas se refiere a las especies clasificadas como Preocupación Menor

(LC) y Casi Amenazado (NT) en la Lista Roja, así como a las especies en las

categorías No Evaluado (NE) y Datos Insuficientes (DD) clasificadas como no

amenazadas por el random forest.

Evolutionarily

and ecologically distinct species at greatest risk of extinction

The phylogenetic diversity (PD) across

trees was 900.96 ± 24.01 MY (mean ± SD). Species with the highest mean ED2

scores were Scleria corymbosa,

Scleria lithosperma and Scleria melanomphala with 22.28, 20.89

and 19.04 MY, respectively. The species with the

greatest mean EDGE2 score was Scleria

porphyrocarpa with

3.97 MY of avertable expected PD loss, followed by Scleria zambesica (2.53 MY), Scleria pulchella (2.25 MY) and Scleria madagascariensis (2.04 MY).

We detected 45

EDGE2 Scleria species (17.24% of species in the genus). Safeguarding

these species, we would secure 68.24% (41.49 MY) of avertable expected PD loss

in a 50-year time horizon. The main list included 23 species (Table 1), of

which 17 belong to section Hypoporum, three to section Acriulus,

two to section Abortivae and one to Corymbosae. The EDGE2

borderline and watch lists included 17 and 5 species respectively (Table A2 of Appendix). The watch list included widespread and locally abundant species

that belong to evolutionary distinctive sections such as S. lithosperma, S. melanomphala and S. tonkinensis.

Table 1. EDGE2 main list, i.e., threatened

species that scored above the median EDGE2 score of the entire genus at least

95% of the time. Species are ranked based on their EDGE2 score. IUCN RL: Red

List category of published species (RL IUCN: DD Data Deficient, VU Vulnerable,

EN Endangered, CR Critically Endangered), and preliminary assessment of Not

Evaluated species (i.e., Threatened). EDGE2: Evolutionarily Distinct and

Globally Endangered metric, ED2: evolutionary distinctiveness.

Tabla 1. Lista

principal EDGE2: especies amenazadas que obtuvieron una puntuación superior a

la mediana de la puntuación EDGE2 de todo el género al menos el 95% de las

veces. Las especies están ordenadas en función de su puntuación EDGE2. IUCN RL:

categoría de la Lista Roja de las especies publicadas (RL IUCN: DD Datos

Insuficientes, VU Vulnerable, EN En Peligro, CR En Peligro Crítico), y

evaluación preliminar de especies No Evaluadas. EDGE2: índice de Especies

Evolutivamente Distintas y Globalmente Amenazadas, ED2: distintividad evolutiva.

Scleria

species with the highest mean FUD scores were Scleria skutchii, the tallest species in the genus, and Scleria depressa, the species with the largest nutlet. Overall, 6 of 10 species with

the highest FUD scores belonged to the sections Ophryoscleria and Schizolepis

which include stout perennials with large leaf areas and climbers. The species

with the greatest mean EcoDGE score was Scleria porphyrocarpa, followed by Scleria tropicalis, Scleria williamsii and Scleria chlorantha. We found 38 EcoDGE species,

6 in the main list (Table 2) and 32 in the borderline EDGE2 species list (Table A3 of Appendix). These species (14.56% of species of the genus) account for 64.28%

of avertable expected functional diversity loss in the genus in a 50-year time

horizon.

The

evolutionary distinctiveness (ED2) metric was a poor explanatory variable of functional

distinctiveness (FUD) in Scleria (F1,237=0.03, p=0.86).

Table 2. EcoDGE main list, i.e., threatened

species that scored above the median EcoDGE score of the entire genus at least

95% of the time. Species are ranked based on their EcoDGE score. IUCN RL: Red

List category of published species (RL IUCN: CR Critically Endangered), and

preliminary assessment of Not Evaluated species (i.e., Threatened). EcoDGE:

Ecologically Distinct and Globally Endangered metric, FUD: functional

distinctiveness.

Tabla 2. Lista

principal de EcoDGE: especies amenazadas que obtuvieron una puntuación superior

a la mediana de la puntuación EcoDGE de todo el género al menos el 95% de las

veces. Las especies están ordenadas en función de su puntuación EcoDGE. IUCN

RL: categoría de la Lista Roja de las especies publicadas (RL IUCN: CR En

Peligro Crítico), y evaluación preliminar de especies No Evaluadas. EcoDGE:

Especies Ecológicamente Distintas y Globalmente Amenazadas, FUD: distintividad

funcional.

Regions of special interest for

conservation

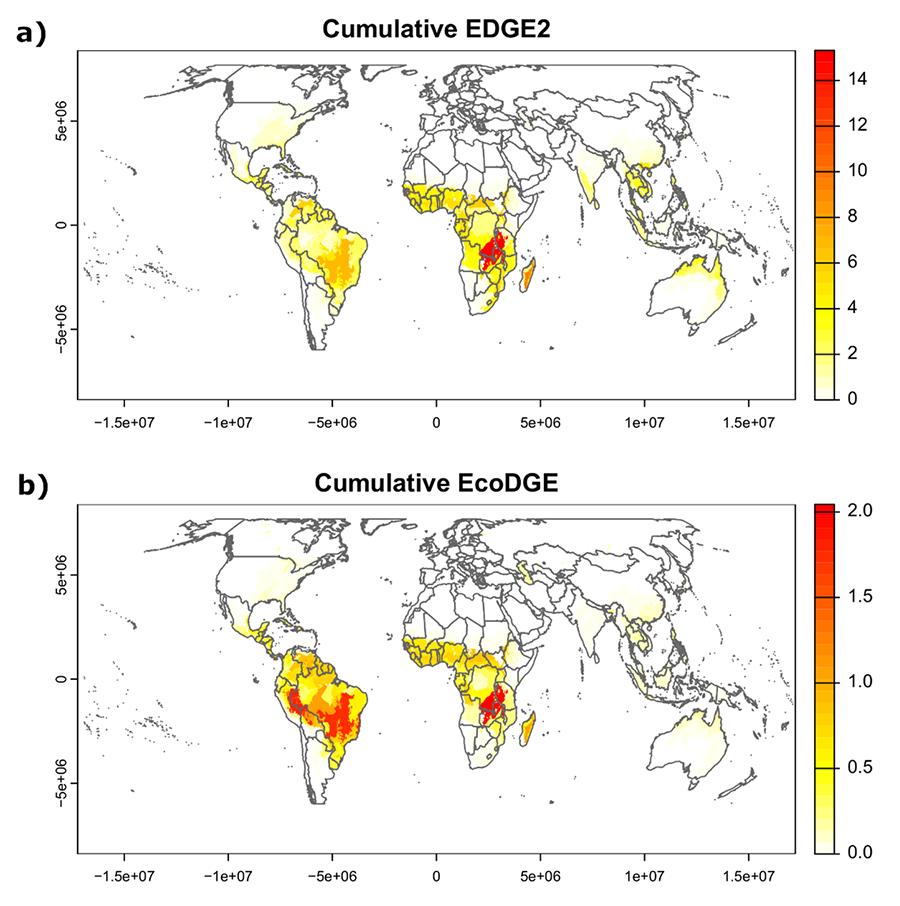

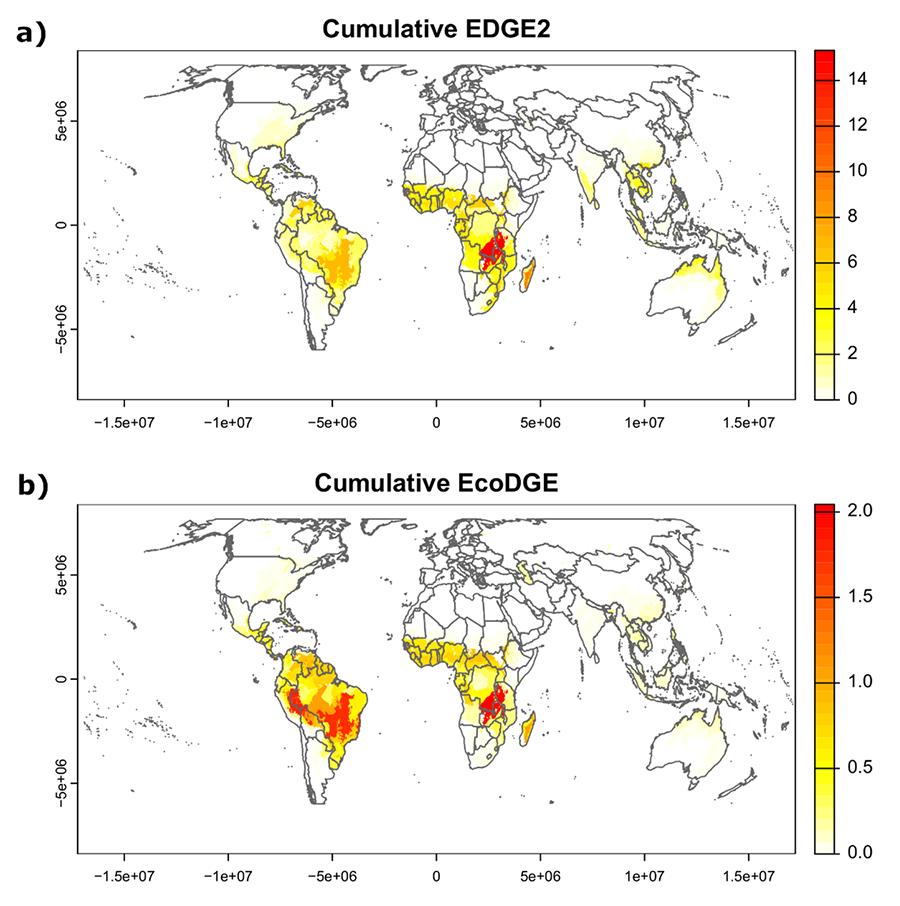

The countries with the highest sum of EDGE2

scores and the greatest number of listed EDGE2 species were Madagascar,

Democratic Republic of the Congo, Brazil, Zambia and Tanzania (Table 3).

The ecoregions with the highest sum of EDGE2 scores and the greatest number of

listed EDGE2 species were the Central Zambezian Miombo woodlands, Madagascar

subhumid forests, Cerrado, East Sudanian savanna, Llanos, Guinean

forest-savanna mosaic and Madagascar lowland forests (Table 4; Fig. 2a).

The countries with the highest cumulative

EcoDGE scores were Brazil, Venezuela, Bolivia, Democratic Republic of the

Congo, Peru and Colombia. The countries with the greatest number of listed

EcoDGE species were Democratic Republic of the Congo, Brazil and Madagascar (Table 3).

The ecoregions with the highest sum of EcoDGE scores and number of listed

EcoDGE species were Central Zambezian Miombo woodlands, Southwest Amazon moist

forests, Bahia coastal forests, Cerrado and Western Congolian forest-savanna

mosaic (Table 4; Fig. 2b).

According to the assessment of the extent

of remaining natural habitat and protected land in the world ecoregions by Dinerstein et al. (2017), there are 22 Scleria

species which are restricted to ‘Nature Imperiled’ ecoregions (i.e., ecoregions

where the percentage of natural habitat remaining and the amount of the total

ecoregion that is protected is less than or equal to 20%) and 34 species only

occur in ecoregions where ‘Nature Could Recover (i.e., ecoregions where the

percentage of natural habitat remaining and area protected is less than 50% but

more than 20% and that require restoration programs to reach the 50% of natural

habitat).

Table 3. Top 20 countries in which Scleria

is present ranked by their sum of EDGE2 scores. Richness: number of species

present, N: number of EDGE2 and EcoDGE species, Main: number of species

included in the main EDGE2 and EcoDGE lists, Sum: sum of EDGE2 and EcoDGE

scores. Expanded results can be found in Table A4 of Appendix.

Tabla 3. Los 20

países con mayor riqueza de Scleria ordenados por la suma de sus

puntuaciones EDGE2. Riqueza: número de especies presentes, N: número de

especies EDGE2 y EcoDGE, Main: número de especies incluidas en las listas

principales EDGE2 y EcoDGE, Sum: suma de las puntuaciones EDGE2 y EcoDGE. Los resultados

ampliados se encuentran en la Tabla A4 del Apéndice 4.

Table 4. Top 20 ecoregions in which Scleria is present ranked by

their sum of EDGE2 scores. Richness: number of species present, N: number of

EDGE2 and EcoDGE species, Main: number of species included in the main EDGE2

and EcoDGE lists, Sum: sum of EDGE2 and EcoDGE scores. Expanded results

can be found in Table A5 of

Appendix.

Tabla 4. Las 20

principales ecorregiones en las que está presente Scleria clasificadas

por su suma de puntuaciones EDGE2. Riqueza: número de especies presentes, N:

número de especies EDGE2 y EcoDGE, Main: número de especies incluidas en las

listas principales EDGE2 y EcoDGE, Sum: suma de las puntuaciones EDGE2 y

EcoDGE. Los resultados ampliados se encuentran en la Tabla

A5 del Apéndice 5.

Figure 2. Ecoregions of notable conservation concern for Scleria according to

their sum of EDGE2 scores (a) and sum of EcoDGE scores (b). The definition of ecoregion follows Olson et al. (2001).

Figura 2. Ecorregiones de notable interés

para la conservación de Scleria según su suma de puntuaciones EDGE2 (a)

y suma de puntuaciones EcoDGE (b). La definición de

ecorregión se basa en Olson et

al. (2001).

Discussion

In this study, we estimated the extinction

risk for all species of the genus Scleria, as well as identified regions

of special interest for its conservation. Our results suggest that half of Scleria

species (49%, N=38) not yet included in the Red List are potentially threatened

with extinction. Evolutionary and ecologically distinct and endangered Scleria

mostly occur across African and South American regions.

Preliminary assessments

Similar to previous studies, RF

outperformed the method that explicitly followed Red List criterion B (Nic Lughadha et al. 2019) and distribution range properties were the

best predictors for RF (Nic Lughadha

et al. 2019; Bachman et al. 2023; Walker et al. 2023). Up to 15 species were classified as threatened by rCAT and

non-threatened by RF; thus, RF set lower thresholds of extent of occurrence

(EOO) to classify Scleria species as threatened. This seems a sensible

approach to assess Scleria because the size of the distribution range as

estimated from herbarium collections is potentially underestimated in most

cases (see below), and widespread and locally dominant species are common (Holm et al.

1979; Galán Díaz et al. 2019).

Considering species included in the Red

List and the results of RF, 26% of all Scleria species are potentially

threatened with extinction. In a recent study, Bachman et al. (2023) obtained a similar

estimate for Cyperaceae. They also found that, of the 21 families with more

than 3000 species, Cyperaceae showed the smallest proportion of threatened

species. Whereas 18% of Scleria species currently included in the Red

List are threatened, we found that 49% of unassessed species are potentially

threatened with extinction. This could be because several Madagascan and South

American Scleria species discovered over the last four decades were

classified as threatened by RF, which might support

that newly described species are geographically restricted and therefore less

likely to be encountered in the wild (Brown et al. 2023). This is the case of Scleria

nusbaumeri, Scleria

ankaratrensis, Scleria attenuatifolia, Scleria chasmema, Scleria millespicula, Scleria pernambucana, Scleria rubrostriata and Scleria tropicalis. It is therefore necessary to

prioritize the assessment of all unassessed species to get realistic estimates

of extinction risk in the genus and to galvanize conservation support for these

species.

Evolutionarily distinct and

globally endangered Scleria

Our analysis identified 23 species that met

the criteria to be included in the EDGE2 main list. Scleria porphyrocarpa

was the species with the highest EDGE2 and ED2 scores due to its high

vulnerability (i.e., it was classified as threatened by both rCAT and RF) and

high evolutionary distinctiveness. Scleria porphyrocarpa belongs to

section Corymbosae, the oldest lineage in subgenus Scleria (crown

age 22.28 Ma) which only includes four other species (Bauters et al.

2016, Larridon et al. 2021). Section Hypoporum was represented in the EDGE2 main list by

17 species. This is due to two reasons: (i) molecular analyses indicated that

section Hypoporum originated 8.4 Ma and showed a rapid increase in its

diversification rate soon after (Larridon et

al. 2021) to become the

richest section in Scleria (Bauters

et al. 2019); (ii) it

holds the highest percentage of threatened species among Scleria

sections according to the Red List and our preliminary assessments (42%; Fig. 1b).

This is important in the context of the new EDGE formulation, that accounts for

the extinction risk of closely related species, because the deeper branches of

a clade with a high proportion of threatened species will have a greater

probability of being at risk, thus resulting in species belonging to it having

higher EDGE scores (Gumbs et al.

2023). Finally, the three

threatened species of section Acriulus were also included in the main

list, as well as two Madagascan endemics from section Abortivae.

Almost half of Scleria

species (129 species) are present in the 11 ecoregions with the greatest

cumulative EDGE2 scores. Four African (Madagascar, D.R. Congo, Zambia and

Tanzania) and two South American (Brazil, Venezuela) countries mainly covered

these areas of special interest for conservation. Madagascar comprises 24

species of Scleria in two ecoregions (i.e., subhumid and lowland

forests), including five threatened and two recently described species.

Madagascan species belong to 11 sections out of the 17 sections recognized in Scleria,

which highlights the importance of this country as a reservoir of Scleria

diversity and the importance of long-distance dispersal in the genus (Galán Díaz et al. 2019). Four other

ecoregions from the Afrotropics (i.e., Central Zambezian Miombo woodlands, East

Sudanian Savanna, Guinean forest-savanna mosaic, and Northwestern Congolian

lowland forests and Zambezian and Mopane woodlands; Olson et al. 2001)

are identified as important conservation areas for Scleria. These

ecoregions contain 67 species (26% species of Scleria, from 12 sections)

of which 19 are endangered.

Brazil has the greatest

Scleria richness (63 species) and ranks second in terms of cumulative EDGE2

scores. Two Brazilian ecoregions are shown as areas of special interest for the

conservation of the evolutionary history of Scleria: Cerrado and Mato

Grosso seasonal forests. These ecoregions include 49 species from 11 sections,

of which 4 are endangered. The Venezuelan Llanos is another important ecoregion

for evolutionary distinct and endangered Scleria. Unlike the Colombian

Llanos, which also includes over 30 species, it includes species from old Scleria

lineages (i.e., sections Lithospermae and Foveolidia; Larridon et al. 2021)

and two threatened species.

According to the

revision of the world ecoregions of Dinerstein et al. (2017), which considered the World Database of Protected Areas (UNEP-WCMC y IUCN 2023) along with habitat assessments based on tree

cover and human land use, two of the above-mentioned ecoregions (i.e.,

Madagascar subhumid forests and Guinean forest-savanna mosaic) are classified

as ‘nature imperiled’ because the percentage of natural habitat remaining and protected area is less

than 20%. Other ecoregions of interest for Scleria conservation that

need active restoration programs to reach the 50% of protected natural habitat

are Madagascar lowland forests, Central Zambezian Miombo woodlands and East

Sudanian savanna.

Ecologically distinct and

globally endangered Scleria

We expect uncertainty

in the identification of EcoDGE species because the results are largely

dependent on the selection of traits, whereas the evolutionary relationship

among Scleria species is well resolved at least at

the section level (Bauters et al. 2016, 2018a). In this study we used traits which are

informative of species ecological strategies (Westoby 1998): plant longevity, leaf area, height and

nutlet size. These traits indicate how plants cope with environmental nutrient

stress and disturbances, the position of the species in the vertical light

gradient of the vegetation, competitive vigor, dispersal distance and seed

persistence in the soil bank (Pérez-Harguindeguy

et al. 2013). We found

ED2 and FUD were largely orthogonal; thus, EcoDGE based prioritizations yielded

complementary results to the EDGE2 approach.

Our analysis identified six species in the

main EcoDGE list. Unlike EDGE2, EcoDGE mostly points towards South American

countries as reservoirs of distinctive and endangered species. This is because

many EDGE2 species are phylogenetically restricted to section Hypoporum which

has its center of diversity in tropical Africa, whereas EcoDGE species (i.e.,

those with great blade area and nutlet size) belong to different sections

mostly restricted to South America. Eight South and Central American countries

are ranked among the top 10 countries with the highest cumulative EcoDGE

scores: Brazil, Venezuela, Bolivia, Peru, Colombia, Guyana, Dominican Republic

and Costa Rica. This is due to the occurrence of stout species from three

sections that are restricted or almost restricted to the Neotropics (Bauters

et al. 2016): sections

Schizolepsis (12 species), Ophryoscleria (11 species) and Hymenolytrum

(13 species). Within these countries, the ecoregions that showed the greatest

cumulative EcoDGE scores were Southwest Amazon moist forests, Bahia coastal

forests, Cerrado and Iquitos Varzeá (87 species in total). The percentage of

natural habitat remaining in these ecoregions is less than 50%, with

restoration programs needed to exceed this threshold (Dinerstein

et al. 2017). D. R.

Congo and Madagascar were the African countries with the highest cumulative

EcoDGE score.

Limitations

Preliminary assessments are biased

by the uncertainty and coverage of the taxonomic and geographical dimensions of

the occurrence datasets (Meyer et al.

2016). We expect little

uncertainty in the taxonomic dimension of our occurrence dataset because the

records have been manually curated and homogenized using the latest list of

accepted species names. Yet, there is a bias in the geographical coverage of Scleria

collections, where the available resources for each country vary greatly and

affect the density of observations as well as the number of specimens collected

and digitized. For instance, the United States of America and Australia are the

countries with the highest average number of Scleria observations per

species with 276 and 273 respectively, which is five times more than the third

and fourth countries in this ranking (Brazil and Mexico). However, the United

States of América and Australia rank 33rd and 11th in

terms of Scleria richness, whereas Brazil and México rank first and

thent. This affects the assessments of species from less explored regions by

potentially leading to an underestimation of the size of their distribution

ranges and a subsequent overestimation of their extinction risk (Nic Lughadha

et al. 2019). In

addition, the United States of America and Australia harbor two nearly endemic Scleria

subgenera (subgenera Trachylomia and Browniae, respectively).

Thus, the quality and quantity of Scleria collections do not only impact

the comprehensiveness of regional floras but it is also unevenly distributed

across the phylogeny. This uncertainty must be considered in biogeographical

studies.

There are also substantial differences in

the completeness of our knowledge of the genus Scleria among neighboring

countries. The identification of regions from Africa as areas of special

interest for the conservation of Scleria reflects their great diversity as

centers of diversification (Larridon et al. 2021), but also our more

comprehensive taxonomic knowledge of this group in particular countries. For

instance, Scleria from Zambia, South Africa and Madagascar are better studied

compared to other African countries thanks to the work of E.A. Robinson (Robinson 1966), E.F. Franklin Hennessy (Franklin Hennessy 1985) and H. Chermezon

(Chermezon 1937). Thus, remarkable patterns of

species richness in these countries might reflect different botanical

collection efforts rather than true species accumulation.

Finally, this study evaluates species and

ecosystems as individual elements, but modern biodiversity conservation

strategies will benefit from a thorough analysis of the eco-social landscape (Butler et al. 2022). On the one hand, the taxonomy of nut rushes is well-resolved (Bauters et al. 2016), but it still is a

little-studied genus in terms of its ecological and economic value. In a recent

bibliographical research, we found that nut rushes reported to have ecological

and economic values tend to be widespread (Galán Díaz et al. 2024), sometimes even

weeds that thrive in disturbed areas (Holm et al. 1979). Thus, we would

hypothesize that the conservation of these species will not be imperiled by

human activity. Still, the genus encompasses many narrow endemics and new

species are continuously discovered in poorly explored areas (Bauters et al. 2015; Mayedo y Thomas 2016; Bauters et al.

2018a; Bauters et al. 2018b; Galán Díaz et al. 2019; Schneider y

Gil 2021; Larridon et al. 2024). This geographical

bias in the coverage of Scleria collections previously commented on can be

tackled by collaborating with local researchers and communities in its

collection and taxonomic study (Heywood

2017). In regard, it is worth mentioning that

Scleria is mainly distributed across tropical areas but articles are often

published in subscription journals (for instance Lye y Pollard 2003; Strong 2007; Araújo y Brummitt 2011; Bauters et al.

2018b). This makes access to new findings

challenging for researchers from the Global South (Pettorelli et al. 2021). Thus, researchers from

the Global North have the responsibility to make papers and data freely

available worldwide for the sake of biodiversity conservation.

Conclusions

We provided the first global assessment of

species and world regions of remarkable interest for Scleria

conservation. We show that recent methodological advances in the identification

of species at-risk of extinction in combination with herbarium data allow the

implementation of the novel EDGE2 and EcoDGE frameworks in plant groups with

well-resolved taxonomies. We found that half of Scleria species not yet

included in the Red List are potentially at risk of extinction, and 21.5% of

the species in the genus are restricted to ecoregions where the percentage of

natural habitat is less than 50%. Phylogenetic and functional distinctiveness

metrics were largely uncorrelated and EDGE2 and EcoDGE metrics point toward

tropical regions of Africa and South America, respectively, as reservoirs of

distinctive and endangered species.

Data Accessibility

The data used to produce this study are

publicly available at Zenodo (Galán Díaz

et al. 2024).

The codes generated during the current

study are available at GitHub (https://github.com/galanzse/Scleria_EDGE).

Authors' contributions

JGD and IL originally formulated the idea.

JGD, HR and IL gathered and curated the data. JGD, SPB, FF and ME performed

statistical analyses. JGD, SPB, FF, ME, HR and IL wrote the manuscript. JGD and

IL acquired funding.

Funding, permissions required,

potential conflicts of interest and acknowledgements

This project was funded by the Spanish

Association of Terrestrial Ecology and ACOM LAB (Agrocomponentes). JGD

is supported by a Margarita Salas fellowship funded by the Spanish Ministry of

Universities and the European Union-Next Generation Plan (MSALAS-2022-22319).

The authors declare that they have no

conflict of interest.

We thank Martin Xanthos from the Royal

Botanic Gardens Kew, Germinal Rouhan and Thomas Haevermans from the Muséum

National d'Histoire Naturelle and the Spanish Ecological Association of

Terrestrial Ecology.

References

Araújo, A.C.,

Brummitt, N.A. 2011. Scleria rubrostriata, a

new species of Cyperaceae from the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Kew Bulletin 66:

517-520. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12225-012-9321-4

Bachman,

S.P., Brown, M.J.M., Leão, T.C.C., Lughadha, E.N., Walker, B.E. 2023.

Extinction risk predictions for the world’s flowering plants to support their

conservation. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.29.555324

Bauters, K., Meganck, K., Vollesen, K., Goetghebeur, P., Larridon, I. 2015.

Scleria pantadenia and Scleria tricristata: Two new species of

Scleria subgenus hypoporum (Cyperaceae, Cyperoideae, Sclerieae) from

Tanzania. Phytotaxa 227: 45-54. https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.227.1.5

Bauters, K., Asselman, P., Simpson, D.A., Muasya, A.M., Goetghebeur, P.,

Larridon, I. 2016. Phylogenetics, ancestral state reconstruction, and a new

infrageneric classification of Scleria (Cyperaceae) based on three DNA markers.

Taxon 65: 444-466. https://doi.org/10.12705/653.2

Bauters, K., Goetghebeur, P., Asselman, P., Meganck, K., Larridon, I. 2018a.

Molecular phylogenetic study of Scleria subgenus Hypoporum (Sclerieae,

Cyperoideae, Cyperaceae) reveals several species new to science. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0203478

Bauters, K., Goetghebeur, P., Larridon, I. 2018b. Scleria cheekii, a

new species of Scleria subgenus Hypoporum (Cyperaceae,

Cyperoideae, Sclerieae) from Cameroon. Kew Bulletin 73: 27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12225-018-9752-7

Bauters, K.,

Larridon, I., Goetghebeur, P. 2019. A taxonomic study of scleria subgenus

hypoporum: Synonymy, typification and a new identification key. Phytotaxa 394: 1-49. https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.394.1.1

Booth, T.H., Nix, H.A., Busby, J.R., Hutchinson, M.F. 2014. bioclim: the

first species distribution modelling package, its early applications and

relevance to most current MaxEnt studies. Diversity and Distributions

20: 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.12144

Brown, M.J.M.M., Bachman, S.P., Nic Lughadha, E. 2023. Three in four

undescribed plant species are threatened with extinction. New Phytologist

240: 1340-1344. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.19214

Butler, E.P., Bliss-Ketchum, L.L., de Rivera, C.E., Dissanayake, S.T.M.,

Hardy, C.L., Horn, D.A., Huffine, B., et al. 2022. Habitat, geophysical, and

eco-social connectivity: benefits of resilient socio–ecological landscapes. Landscape

Ecology 37: 1-29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-021-01339-y

Chermezon, H. 1937. Cypéracées (29º Familie). En: Humbert, H. (ed.), Flore

de Madagascar et des Comores, Tananarive, Imprimerie officielle.

Antananarivo, Madagascar.

CIESIN 2016. Gridded Population of the World, Version 4 (GPWv4): Population

Density. Center for International Earth Science Information Network, Columbia

University. New York, USA. https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/data/catalog/sedac-ciesin-sedac-gpwv4-popcount-r11-4.11

Cowell, C.R., Bullough, L.-A., Dhanda, S., Harrison Neves, V., Ikin, E.,

Moore, J., Purdon, R., et al. 2022. Fortuitous Alignment: The Royal

Botanic Gardens, Kew and the Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability

14: 2366. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042366

Davidse, G., Sánchez, M.S., Chater, A.O. 1994. Flora mesoamericana (Vol.

6). Alismataceae a Cyperaceae. UNAM, Missouri Botanical Garden and The

Natioanl History Museum, London, United Kingdom.

Dinerstein, E., Olson, D., Joshi, A., Vynne, C., Burgess, N.D., Wikramanayake,

E., Hahn, N., et al. 2017. An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half

the Terrestrial Realm. BioScience 67: 534-545. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/bix014

Forest, F., Moat, J., Baloch, E., Brummitt, N.A., Bachman, S.P.,

Ickert-Bond, S., Hollingsworth, P.M., et al. 2018. Gymnosperms on the

EDGE. Scientific Reports 8: 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-24365-4

Franklin Hennessy, E.F. 1984. The genus Scleria

in southern Africa. Bothalia 530: 505-530. https://doi.org/10.4102/abc.v15i3/4.1829

Galán Díaz, J., Bauters,

K., Rabarivola, L., Xanthos, M., Goetghebeur, P., Larridon, I., Díaz, J.G.,

et al. 2019. A revision of scleria (Cyperaceae) in

Madagascar. Blumea: Journal of Plant Taxonomy and Plant Geography 64:

195-213.

Galán Díaz, J., Bauters,

K., Escudero, M., Larridon, I. 2024. Taxonomy, occurrences,

phylogeny, traits and uses of the entire plant genus Scleria (Cyperaceae) [Data set]. Available at: https://zenodo.org/records/12755860

GBIF 2023. GBIF Occurrence Download. Available at: https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.wvy3nc

[accessed 13/08/2023].

Govaerts, R., Nic Lughadha, E., Black, N., Turner, R., Paton, A. 2021. The

World Checklist of Vascular Plants, a continuously updated resource for

exploring global plant diversity. Scientific Data 8: 215. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-021-00997-6

Gower, J.C. 1971. A general coefficient of similarity and some of its properties. Biometrics

27: 857–871. https://doi.org/10.2307/2528823

Griffith, P., Lang, J.W., Turvey, S.T., Gumbs, R. 2022. Using functional

traits to identify conservation priorities for the world’s crocodylians. Functional

Ecology 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.14140

Gumbs, R., Gray, C.L., Wearn, O.R., Owen, N.R. 2018. Tetrapods on the

EDGE: Overcoming data limitations to identify phylogenetic conservation

priorities. PLOS ONE 13:

e0194680. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0194680

Gumbs, R., Gray, C.L., Böhm, M., Burfield, I.J., Couchman, O.R., Faith,

D.P., Forest, F., et al. 2023. The EDGE2 protocol: Advancing the

prioritisation of Evolutionarily Distinct and Globally Endangered species for

practical conservation action. PLoS Biology 21: 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3001991

Heywood, V.H. 2017. Plant conservation in the Anthropocene – Challenges and

future prospects. Plant Diversity 39: 314-330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pld.2017.10.004

Hidasi-Neto, J., Loyola, R., Cianciaruso, M.V. 2015. Global

and local evolutionary and ecological distinctiveness of terrestrial mammals:

identifying priorities across scales. Diversity and Distributions 21:

548-559. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.12320

Holm, L., Pancho, J.V., Herberger, J.P., Plucknett, D.L. 1979. A

geographical atlas of world weeds. John Wiley and Sons. New York, USA.

Huang, D. 2012. Threatened Reef Corals of the World Matz, M.V. (ed.),. PLoS ONE

7: e34459. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0034459

iNaturalist community. Research grade observations of

all Scleria species worldwide available on 23/10/2023. [Exported from https://www.inaturalist.org on 23/10/2023].

Isaac, N.J.B., Turvey, S.T., Collen, B., Waterman, C., Baillie, J.E.M.

2007. Mammals on the EDGE: Conservation priorities based on threat and

phylogeny. PLoS ONE 2(3):e296. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0000296

IUCN 2023. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2023-1 [accessed 13/08/2023].

Kondratyeva, A., Grandcolas, P., Pavoine, S. 2019. Reconciling the concepts and

measures of diversity, rarity and originality in ecology and evolution. Biological

Reviews 94: 1317-1337. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12504

Larridon, I. 2022. A linear classification of Cyperaceae. Kew Bulletin 77:

309-315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12225-022-10010-x

Larridon, I., Galán Díaz,

J., Bauters, K., Escudero, M. 2021. What drives

diversification in a pantropical plant lineage with extraordinary capacity for

long-distance dispersal and colonization? Journal of Biogeography 48:

64-77. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.13982

Larridon, I., Bauters, K., Rasaminirina, F., Galán Díaz, J., Márquez-Corro,

J.I., Gautier, L. 2024. A new remarkable species of Scleria

(Cyperaceae) from northern Madagascar. Candollea 79: 107-116. https://doi.org/10.15553/c2024v791a6

Le Roux, M. 2015. The e-Flora of South Africa. Veld & Flora

101: 12.

Losos, J.B. 2008. Phylogenetic niche conservatism, phylogenetic signal and the

relationship between phylogenetic relatedness and ecological similarity among

species. Ecology Letters 11: 995-1003. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2008.01229.x

Lye, K.A., Pollard, B.J. 2003. Studies in African Cyperaceae 29. Scleria

afroreflexa, a new species from western Cameroon. Nordic Journal of Botany

23: 431-435. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-1051.2003.tb00416.x

Mayedo, W.B., Thomas, W.W. 2016. Two New Species of Scleria section

Hypoporum (Cyperaceae) from Espírito Santo, Brazil. Phytotaxa 268: 263. https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.268.4.4.

Meyer, C., Weigelt, P., Kreft, H. 2016. Multidimensional biases, gaps and

uncertainties in global plant occurrence information Lambers, J. H. R. (ed.),. Ecology

letters 19: 992-1006. ttps://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12624

Moat, J. Bachman, S. 2020. rCAT: Conservation

assessment tools. R package version 0.1.6. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rCAT

Mooers, A.Ø., Faith, D.P., Maddison, W.P. 2008. Converting Endangered

Species Categories to Probabilities of Extinction for Phylogenetic Conservation

Prioritization. PLoS ONE 3: e3700. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0003700

Mu, H., Li, X., Wen, Y., Huang,

J., Du, P., Su, W., Miao, S., et al. 2022. A global record of

annual terrestrial Human Footprint dataset from 2000 to 2018. Scientific

Data 9:176. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01284-8

Nic

Lughadha, E., Walker, B.E., Canteiro, C., Chadburn,

H., Davis, A.P., Hargreaves, S., Lucas, E.J., et al. 2019. The use and

misuse of herbarium specimens in evaluating plant extinction risks. Philosophical

Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 374: 20170402. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2017.0402

Olson, D.M.,

Dinerstein, E., Wikramanayake, E.D., Burgess, N.D., Powell, G.V.N., Underwood,

E.C., D’Amico, J.A. et al. 2001. Terrestrial ecoregions of the world: a

new map of life on Earth. Bioscience 51: 933-938. https://doi.org/10.1641/0006-3568(2001)051[0933:TEOTWA]2.0.CO;2

Pérez-Harguindeguy, N., Diaz, S., Garnier, E., Lavorel, S., Poorter, H., Jaureguiberry,

P., Bret-Harte, M.S.S., et al. 2013. New Handbook for standardized

measurement of plant functional traits worldwide. Australian Journal of

Botany 61: 167-234. https://doi.org/10.1071/BT12225

Pettorelli, N., Barlow, J., Nuñez, M.A., Rader, R., Stephens, P.A., Pinfield,

T., Newton, E. 2021. How international journals can support ecology from the

Global South. Journal of Applied Ecology 58: 4-8. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.13815

Ramos-Gutiérrez, I., Lima, H., Vilela, B., Molina-Venegas, R. 2023. A generalized framework to expand incomplete phylogenies using non-molecular phylogenetic information. Global Ecology and Biogeography 1-10.

https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.13733

Robinson, E. 1966. An Account of the Genus Scleria in the Flora Zambesiaca. Kew

Bulletin 18: 487-551. https://doi.org/10.2307/4115799

Safi, K., Armour-Marshall, K., Baillie, J.E.M., Isaac, N.J.B. 2013.

Global Patterns of Evolutionary Distinct and Globally Endangered Amphibians and

Mammals. PLoS ONE 8: e63582. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0063582

Šavrič, B., Patterson, T., Jenny, B. 2019. The Equal Earth map projection.

International Journal of Geographical Information Science 33: 454-465. https://doi.org/10.1080/13658816.2018.1504949

Schneider, L.J.C., Gil, A.D.S.B. 2021. Scleria (Cyperaceae) in the

state of Pará, Amazon, Brazil. Acta Botanica Brasilica 35: 215-247. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-33062020abb0221

Simpson, D.A.,

Inglis, C.A. 2001. Cyperaceae of economic,

ethnobotanical and horticultural importance: a checklist. Kew Bulletin 56: 257

–360.

Simpson,

D.A., Koyama, T. 1998. Flora of Thailand. Vol.

6, part 4, Cyperaceae. Forest Herbarium, Rotal Forest Department, Bangkok.

Thailand.

Smith, J.R., Letten, A.D., Ke, P.-J.J., Anderson, C.B., Hendershot, J.N.,

Dhami, M.K., Dlott, G.A., et al. 2018. A global test of ecoregions. Nature

Ecology and Evolution 2: 1889-1896. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0709-x

Strong, M.T. 2007. Scleria tropicalis (Cyperaceae), A new species

from Northern Andean South America. Harvard Papers in Botany 11:

199-201. https://doi.org/10.3100/1043-4534(2007)11[199:STCANS]2.0.CO;2

UNEP-WCMC,

IUCN. 2023. Protected Planet: The World Database

on Protected Areas (WDPA) and World Database on Other Effective Area-based

Conservation Measures (WD-OECM), [08/2023]. UNEP-WCMC

and IUCN, Cambridge, UK. Availaible at: https://www.protectedplanet.net.

Walker, B.E., Leão, T.C.C., Bachman, S.P., Lucas, E., Nic Lughadha, E.

2023. Evidence-based guidelines for automated conservation assessments of plant

species. Conservation Biology 37: 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13992

Westoby, M.

1998. A leaf-height-seed (LHS) plant ecology strategy scheme. Plant and Soil

199: 213-227. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1004327224729

Zizka, A., Andermann, T., Silvestro, D. 2022. IUCNN – Deep learning

approaches to approximate species’ extinction risk. Diversity and

Distributions 28: 227-241. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.13450

Appendix

Table A1. Combined Red List results. This

includes assessments published in the Red List of the IUCN version 2023-1 (RL

IUCN: NE Not Evaluated, DD Data Deficient, LC Least Concern, NT Near

Threatened, VU Vulnerable, EN Endangered, CR Critically Endangered, EX

Extinct), unpublished assessments (‘Assessed but not published’) and

preliminary assessments (T Threatened, NT Non-threatened) of 67 species for

which occurrence data was available. Preliminary assessments followed two

approaches.

(i) Random forest approach (RF). We used as predictors: EOO, AOO, mean of latitudinal range,

elevation, minimum human population density in 2020 (HPD; Center for International Earth Science Information Network - CIESIN 2016), human footprint index in 2013 (HFI; Mu et al. 2022), proportion of observations located in

protected areas (UNEP-WCMC

and IUCN 2023), annual mean

temperature, minimum temperature of the coldest month, temperature annual

range, annual precipitation, precipitation of the driest month and

precipitation seasonality. We performed 10 repeats of 5-fold cross-validation

to train and evaluate the model and retained 20% of data for external

validation.

(ii)

rCAT. We implemented the function ‘ConBatch’ from

the R package ‘rCAT’ (Moat & Bachman

2020) to assess species’

extinction risk following IUCN Criterion B based on EOO.

Tabla A1. Resultados combinados de riesgo de

extinción. Esto incluye evaluaciones publicadas en la Lista Roja de la UICN

versión 2023-1 (RL UICN: NE No evaluado, DD Datos insuficientes, LC

Preocupación menor, NT Casi amenazado, VU Vulnerable, EN En peligro, CR En

peligro crítico, EX Extinto), evaluaciones no publicadas (‘Assessed but not

published’) y evaluaciones preliminares (Amenazado: T, No amenazado: NT) de 67

especies para las que se disponía de datos de presencia. Las evaluaciones

preliminares siguieron dos enfoques.

(i) Enfoque de bosque aleatorio (RF). Se utilizaron

como predictores EOO, AOO, media del rango latitudinal, elevación, densidad

mínima de población humana en 2020 (HPD; Center for International Earth Science

Information Network - CIESIN 2016), índice de huella

humana en 2013 (HFI; Mu et al. 2022), proporción

de observaciones localizadas en áreas protegidas (UNEP-WCMC

and IUCN 2023), temperatura media anual, temperatura mínima del mes más

frío, rango anual de temperatura, precipitación anual, precipitación del mes

más seco y estacionalidad de la precipitación. Realizamos 10 repeticiones de

validación cruzada con 5 particiones para entrenar y evaluar el modelo y

retuvimos el 20% de los datos para la validación externa.

(ii) rCAT. Implementamos la función 'ConBatch' del

paquete R 'rCAT' (Moat & Bachman 2020) para

evaluar el riesgo de extinción de las especies siguiendo el Criterio B de la

UICN basado en EOO.

Species

without occurrence data / Especies sin datos de presencia: S. assamica (C.B.Clarke) D.M.Verma, S.

depauperata Boeckeler, S. elongatissima Piérart, S. hirta

Boeckeler, S. jiangchengensis Y.Y.Qian, S. lateritica Nelmes, S.

macrolomioides H.Pfeiff., S. mutoensis Nakai, S. papuana

J.Kern, S. scandens Core, S. schenckiana Boeckeler and S.

swamyi Govind.

Table A2. Scleria EDGE2 borderline and watch lists

(Gumbs et al. 2023). Borderline list: threatened

species whose distribution of EDGE2 scores rank above the median of the entire

genus at least 80% of the time. Watch list: nonthreatened species whose distribution of EDGE2 scores rank above

the median of the entire genus at least 95% of the times. EDGE2: Evolutionarily Distinct and

Globally Endangered metric, ED2: evolutionary distinctiveness.

Tabla A2. Listas límite y de vigilancia EDGE2

de Scleria (Gumbs et al. 2023). Lista

límite: especies amenazadas cuya distribución de las puntuaciones EDGE2 se

sitúa por encima de la mediana de todo el género al menos el 80% de las veces.

Lista de vigilancia: especies no amenazadas cuya distribución de las

puntuaciones EDGE2 se sitúa por encima de la mediana de todo el género al menos

el 95% de las veces. EDGE2: Métrica de distintividad evolutiva y en peligro de

extinción a escala mundial, ED2: Métrica de distintividad evolutiva.

Table A3. Scleria EcoDGE borderline list (Griffith et al.

2022; Gumbs et al. 2023): threatened species whose distribution of EcoDGE scores rank above

the median of the entire genus at least 80% of the time. EcoDGE: Ecologically

Distinct and Globally Endangered metric, FUD: functional distinctiveness.

Tabla A3. Lista límite EcoDGE de Scleria

(Griffith et al. 2022; Gumbs

et al. 2023): especies amenazadas cuya distribución de puntuaciones EcoDGE

se sitúa por encima de la mediana de todo el género al menos el 80% de las

veces. EcoDGE: Métrica de distintividad ecológica y en peligro de extinción a

escala mundial, FUD: distintividad funcional.

Table A4. Countries in which Scleria is present ranked by their sum

of EDGE2 scores. Richness: number of species present, N: number of listed EDGE2

and EcoDGE species, Main: number of species included in the main EDGE2 and

EcoDGE lists, Sum: sum of EDGE2 and EcoDGE scores.

Tabla A4. Países en los que Scleria

está presente ordenados por su suma de puntuaciones EDGE2. Richness: número de

especies presentes, N: número de especies incluidas en las listas EDGE2 y

EcoDGE, Main: número de especies incluidas en las listas principales EDGE2 y

EcoDGE, Sum: suma de las puntuaciones EDGE2 y EcoDGE.

|

Country

|

Richness

|

EDGE2

|

EcoDGE

|

|

N

|

Main

|

Sum

|

N

|

Main

|

Sum

|

|

Madagascar

|

24

|

7

|

3

|

10.11

|

3

|

0

|

1.24

|

|

Dem. Rep. Congo

|

26

|

5

|

2

|

9.85

|

5

|

0

|

1.94

|

|

Brazil

|

63

|

6

|

2

|

9.43

|

4

|

2

|

3.08

|

|

Zambia

|

29

|

5

|

4

|

8.95

|

1

|

0

|

0.79

|

|

Tanzania

|

30

|

5

|

3

|

8.23

|

2

|

0

|

0.63

|

|

Venezuela

|

31

|

3

|

1

|

5.94

|

1

|

1

|

2.00

|

|

South Africa

|

17

|

2

|

0

|

5.23

|

0

|

0

|

0.17

|

|

Thailand

|

20

|

3

|

1

|

5.18

|

0

|

0

|

0.28

|

|

China

|

15

|

3

|

0

|

4.76

|

0

|

0

|

0.24

|

|

Bolivia

|

34

|

1

|

0

|

4.33

|

1

|

0

|

1.98

|

|

Guinea

|

15

|

4

|

2

|

4.29

|

1

|

0

|

0.22

|

|

Ghana

|

20

|

2

|

0

|

4.20

|

0

|

0

|

0.68

|

|

Ethiopia

|

16

|

4

|

1

|

4.20

|

0

|

0

|

0.29

|

|

Côte d'Ivoire

|

20

|

2

|

0

|

4.05

|

0

|

0

|

0.66

|

|

Philippines

|

13

|

3

|

0

|

3.96

|

1

|

0

|

0.32

|

|

Gabon

|

19

|

3

|

1

|

3.95

|

2

|

0

|

0.66

|

|

Angola

|

11

|

2

|

1

|

3.83

|

1

|

0

|

0.32

|

|

Nigeria

|

20

|

2

|

0

|

3.74

|

0

|

0

|

0.63

|

|

Guyana

|

21

|

1

|

0

|

3.58

|

1

|

0

|

1.26

|

|

Cameroon

|

18

|

3

|

0

|

3.56

|

2

|

0

|

0.89

|

|

Australia

|

22

|

1

|

0

|

3.51

|

1

|

0

|

0.30

|

|

Zimbabwe

|

8

|

2

|

1

|

3.50

|

1

|

0

|

0.21

|

|

Colombia

|

32

|

1

|

0

|

3.47

|

0

|

0

|

1.41

|

|

Mozambique

|

7

|

2

|

0

|

3.45

|

0

|

0

|

0.23

|

|

India

|

13

|

2

|

0

|

3.45

|

2

|

0

|

0.51

|

|

Mexico

|

23

|

1

|

0

|

3.39

|

0

|

0

|

0.54

|

|

Cuba

|

22

|

1

|

0

|

3.26

|

0

|

0

|

0.36

|

|

Indonesia

|

15

|

1

|

0

|

3.14

|

1

|

1

|

0.40

|

|

Belize

|

16

|

1

|

0

|

3.03

|

0

|

0

|

0.42

|

|

eSwatini

|

6

|

2

|

0

|

2.94

|

0

|

0

|

0.07

|

|

Guatemala

|

13

|

1

|

0

|

2.83

|

0

|

0

|

0.44

|

|

Nicaragua

|

15

|

1

|

0

|

2.82

|

0

|

0

|

0.45

|

|

Honduras

|

16

|

1

|

0

|

2.80

|

0

|

0

|

0.46

|

|

Costa Rica

|

17

|

1

|

0

|

2.70

|

0

|

0

|

0.98

|

|

Trinidad and Tobago

|

13

|

1

|

0

|

2.62

|

1

|

1

|

0.74

|

|

Liberia

|

10

|

2

|

1

|

2.58

|

0

|

0

|

0.18

|

|

Burkina Faso

|

11

|

1

|

0

|

2.51

|

0

|

0

|

0.53

|

|

Benin

|

18

|

1

|

0

|

2.50

|

0

|

0

|

0.61

|

|

Peru

|

24

|

1

|

0

|

2.45

|

1

|

0

|

1.53

|

|

Eq. Guinea

|

9

|

2

|

1

|

2.42

|

1

|

0

|

0.31

|

|

Uganda

|

11

|

1

|

0

|

2.36

|

0

|

0

|

0.27

|

|

Botswana

|

8

|

1

|

0

|

2.27

|

0

|

0

|

0.08

|

|

Togo

|

12

|

1

|

0

|

2.16

|

0

|

0

|

0.56

|

|

Dominican Rep.

|

8

|

2

|

0

|

2.08

|

1

|

0

|

1.01

|

|

United States of America

|

14

|

1

|

0

|

2.06

|

0

|

0

|

0.12

|

|

Malawi

|

6

|

1

|

1

|

2.01

|

0

|

0

|

0.21

|

|

Taiwan

|

8

|

1

|

0

|

1.95

|

0

|

0

|

0.09

|

|

Sri Lanka

|

6

|

1

|

0

|

1.84

|

0

|

0

|

0.04

|

|

Argentina

|

12

|

1

|

0

|

1.83

|

0

|

0

|

0.39

|

|

Puerto Rico

|

11

|

1

|

0

|

1.77

|

0

|

0

|

0.25

|

|

Sierra Leone

|

8

|

1

|

1

|

1.68

|

0

|

0

|

0.10

|

|

Panama

|

15

|

0

|

0

|

1.65

|

1

|

0

|

0.96

|

|

Congo

|

11

|

1

|

0

|

1.64

|

1

|

0

|

0.33

|

|

Jamaica

|

6

|

1

|

0

|

1.55

|

0

|

0

|

0.16

|

|

Kenya

|

5

|

1

|

0

|

1.48

|

0

|

0

|

0.17

|

|

Paraguay

|

12

|

0

|

0

|

1.47

|

0

|

0

|

0.40

|

|

Central African Rep.

|

10

|

0

|

0

|

1.31

|

0

|

0

|

0.16

|

|

Fiji

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

1.29

|

0

|

0

|

0.01

|

|

Tonga

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

1.29

|

0

|

0

|

0.01

|

|

Suriname

|

17

|

0

|

0

|

1.25

|

0

|

0

|

0.70

|

|

Rwanda

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

1.24

|

0

|

0

|

0.02

|

|

Bahamas

|

1

|

1

|

0

|

1.22

|

0

|

0

|

0.01

|

|

Timor-Leste

|

1

|

1

|

0

|

1.22

|

0

|

0

|

0.01

|

|

Cayman Is.

|

1

|

1

|

0

|

1.22

|

0

|

0

|

0.01

|

|

Ecuador

|

16

|

0

|

0

|

1.17

|

0

|

0

|

0.47

|

|

Guinea-Bissau

|

5

|

0

|

0

|

1.00

|

0

|

0

|

0.09

|

|

Niger

|

2

|

0

|

0

|

0.76

|

0

|

0

|

0.03

|

|

S. Sudan

|

1

|

1

|

0

|

0.74

|

1

|

0

|

0.10

|

|

New Caledonia

|

4

|

1

|

0

|

0.72

|

2

|

1

|

0.28

|

|

Chad

|

4

|

0

|

0

|

0.50

|

0

|

0

|

0.15

|

|

Japan

|

6

|

0

|

0

|

0.49

|

0

|

0

|

0.07

|

|

Mali

|

7

|

0

|

0

|

0.48

|

0

|

0

|

0.47

|

|

Lesotho

|

3

|

0

|

0

|

0.43

|

0

|

0

|

0.01

|

|

Senegal

|

9

|

0

|

0

|

0.41

|

0

|

0

|

0.50

|

|

Nepal

|

3

|

0

|

0

|

0.41

|

0

|

0

|

0.03

|

|

Burundi

|

5

|

0

|

0

|

0.40

|

0

|

0

|

0.16

|

|

Myanmar

|

2

|

0

|

0

|

0.40

|

0

|

0

|

0.02

|

|

El Salvador

|

5

|

0

|

0

|

0.34

|

0

|

0

|

0.06

|

|

Vietnam

|

5

|

0

|

0

|

0.32

|

0

|

0

|

0.07

|

|

Papua New Guinea

|

3

|

0

|

0

|

0.25

|

0

|

0

|

0.02

|

|

Cambodia

|

3

|

0

|

0

|

0.23

|

1

|

0

|

0.08

|

|

Seychelles

|

2

|

0

|

0

|

0.19

|

0

|

0

|

0.04

|

|

Mauritius

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0.19

|

1

|

0

|

0.06

|

|

Vanuatu

|

2

|

0

|

0

|

0.15

|

0

|

0

|

0.01

|

|

Laos

|

2

|

0

|

0

|

0.09

|

0

|

0

|

0.02

|

|

Uruguay

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0.08

|

0

|

0

|

0.00

|

|

Malaysia

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0.02

|

0

|

0

|

0.01

|

|

French Guiana

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0.00

|

0

|

0

|

0.00

|

Table A5. Top

50 ecoregions in which Scleria is present ranked by their sum of EDGE2

scores. Richness: number of species present, N: number of EDGE2 and EcoDGE

species, Main: number of species included in the main EDGE2 and EcoDGE lists,

Sum: sum of EDGE2 and EcoDGE scores.

Tabla A5. Las 50 principales ecorregiones en

las que Scleria está presente según su suma de puntuaciones EDGE2. Richness:

número de especies presentes, N: número de especies EDGE2 y EcoDGE, Main:

número de especies incluidas en las listas principales EDGE2 y EcoDGE, Sum:

suma de las puntuaciones EDGE2 y EcoDGE.

![]() , Steven P.

Bachman3

, Steven P.

Bachman3 ![]() , Félix Forest3

, Félix Forest3 ![]() , Marcial Escudero1

, Marcial Escudero1 ![]() , Hannah Rotton3, Isabel Larridon3,4

, Hannah Rotton3, Isabel Larridon3,4 ![]()